The Writer as Madman and Mystic

Editor's Note: This article is posted courtesy of Patheos Experts.

I spend a lot of time reading what other writers say about writing. It's an excellent way to procrastinate from actually writing. In reading the words of seasoned authors, who themselves are usually writing about writing in order to avoid other projects, I have discovered two recurring themes. The process of writing may very well make you crazy. And it may also make you a mystic.

Sometimes the crazy is the charming kind of crazy, like the retired journalist in my hometown who walked the streets for hours a day, waving at everything that passed by: cars, people, planes, squirrels. Philip Yancey says that the first phase of his writing process "is all psychosis. I don't even subject my wife to it. I go to a cabin in the mountains. I don't shave. I'll go a week without speaking to a single person, except maybe a store clerk. I work really long hours just pounding out junk."

But sometimes the crazy is the life-choking, relationship-poisoning kind of crazy. It doesn't take much experience with the madness of the writing life to understand Hemingway's routine on Key West while writing A Farewell to Arms. The alarm bells start to sound when spending the mornings writing with six-fingered cats, the afternoons getting bombed on cheap scotch, and the evenings shooting at sharks with a Tommy gun begins to sound like a viable lifestyle. Eat Pray Love author Elizabeth Gilbert, pondering that her greatest writing success is likely behind her, confesses "It's enough to make you start drinking gin at 9 in the morning." She laments that the pressures of the creative process have been killing off our artists for the last 500 years.

The writing process is an emotional rollercoaster that threatens to run you right off the rails. Writing is about so much more than sitting down and typing. It's more like a war, as you, your ideas, and your words all battle each other for supremacy. In writing, your hopes, dreams, fears and inadequacies are exposed. You learn what it is you most want in life and how incompetent you are to actually achieve it. It's easy to see how the first casualty of this war is your sanity.

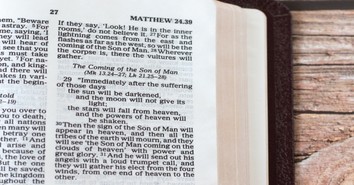

But the process of writing may also make you a mystic. A life of writing can transform the most committed atheist into someone who talks of gods and spirits and muses. Countless authors attest that, in some mysterious way, the discipline of writing can connect us with outside forces, as our words become channels for other voices speaking in the universe. C.S. Lewis said, "I never exactly made a book. It's rather like taking dictation. I was given things to say." Others take a more earthy approach when they claim they don't invent a story, rather they excavate it. They imagine themselves as literary archeologists, discovering a story or an idea that has been buried deep within them yet cries out to be found.

Some writers seek to renew our belief in muses, those ancient spirits that inspire the creativity behind great works of art and music and literature. Elizabeth Gilbert says that in ancient cultures people themselves were not considered geniuses, but they had a genius who sparked their creative impulses. In a different spirit, Stephen King envisions his muse as a fat guy living in his basement, smoking cigars and admiring his bowling trophies and pretending to ignore you. But, says King, "the guy with the cigar and the little wings has got a bag of magic. There's stuff in there that can change your life."

Some people may consider the writer's tendency towards madness and mysticism as one and the same. But from what I can see, the first leads to restlessness and despair while the second moves toward peace and freedom. Gilbert hopes that resurrecting the muse will give writers a necessary distance from their work, releasing them from the destructive side effects of the creative process.

As much as I appreciate Gilbert's views, as a Christian I am not ultimately satisfied with her solution. I agree that there is another power that overlaps with our creative efforts, but for me it is the Holy Spirit. I won't reduce the Holy Spirit to a muse, but I do believe that the same influence that inspired the apostles to preach and write is also, in whatever lesser form, present in my work, even in the very messiness of the writing process. I consider writing a spiritual discipline. It is one of those ancient practices that unfolds our souls and opens our hearts and minds to the God who speaks to us, with us, and through us.

The ancient muses, it was thought, helped create works of art and literature. But the God in whom I believe is about creating certain kinds of people, shaping them into men and women who believe, hope, and love. While I do think God cares about the works we create, I believe that God is more interested in the process and its effect upon us. God is in the dying - the struggle and the wounds and the agony, just as much as he is in the rising - the gleaming product at the end. Out of the chaos of the writing life, God is forming us to be people who are humbled, disciplined, persevering, surprised, grateful. And if, through the writing process, we allow ourselves to be shaped into new kinds of people, then perhaps writers will come to be known for more than just being crazy.

This article is part of the Patheos Expert Series at Patheos.com. Reprinted with permission.

Publication date: December 13, 2010

Originally published December 13, 2010.