What Is a Parable and How Should We Read Them?

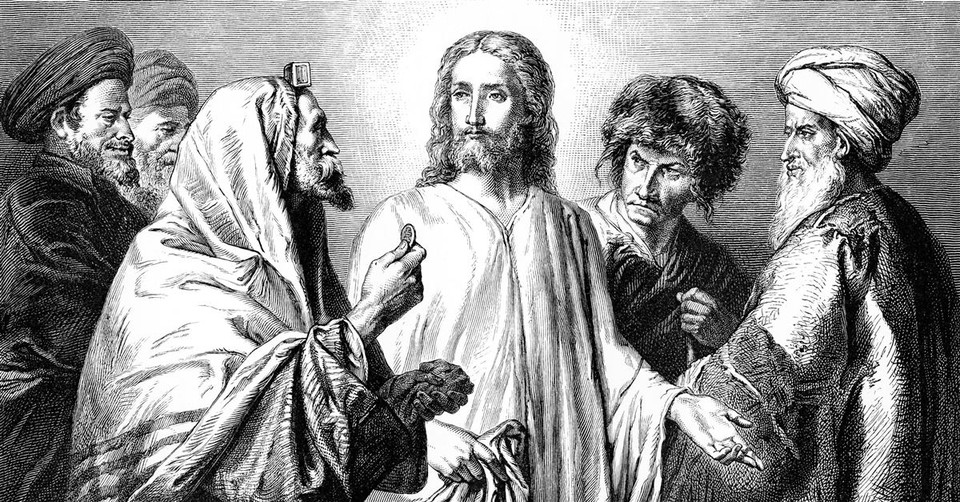

Sprinkled throughout the teachings of Jesus, we find tales of mustard seeds and swine, pearls and wineskins. Narratives of coins and stray sheep, buried treasure and banquets collect within the pages of our Bibles. These colorful parables evoke earthly images we can see to help communicate heavenly meanings that we cannot see. Put simply, a parable is a short story that conveys a greater truth.

While most of Scripture’s parables are found within the Gospels, we do find a few in the Old Testament. For example, the prophet Nathan tells David a story of a rich man stealing a poor man’s sheep to bring out David’s adulterous affair with Bathsheba (

The New Testament contains over 40 parables. These stories illustrate much about the Kingdom of God for those who have ears to hear.

How Were Parables Used in the New Testament?

Jesus used parables in giving instruction, and both revealing and concealing spiritual truths. The parables compared the story shared with the reality of the Kingdom of God. While the first is simple and relatable, the second is profound and consequential. The two together invite comparison that opens up windows of understanding.

While some understood the parables, others did not. In

A Brief History of Parable Interpretation

The parable genre has generated various schools of thought in biblical interpretation. Throughout much of church history prior to this century, most theologians – like those in the Introduction to Biblical Interpretation – argued that parables are allegories and that every character or item within the story is intended to represent something else (p. 411). This tactic produced a multiplicity of interpretations that developed with denominations and traditions. At times, interpretation strayed from what the original audience would or could have understood. The interpretations became so numerous, there was little consensus.

To combat the complications of this abstract strategy, some interpreters over-corrected and began to argue that parables intended only one broad meaning, writes Robert H. Stein (p. 53). The resulting interpretations often diluted the parables’ intricacy and significance.

While each of these positions fall on opposite ends of a spectrum, a centered approach helps ground us in Scripture while still seeking out the full weight of the parable.

How Should We Interpret Parables Today?

In parables with more than one character, it is helpful to look for the main point of each individual. Parables often utilize the figure of a father, manager, or king in representation of God. The remaining characters interact with his authority and grace, and teach us the impact of those responses.

A good student of the Bible seeks to understand the cultural norms and mores of the original audience in harvesting the meaning of the text. Agricultural metaphors could be lost on modern audiences better acquainted with the produce section than their own green thumb, whereas they would be vibrant to the New Testament audience. The parable of the sower that emphasizes a crop’s need for good soil and the power of weeds to choke out life would have resonated with Jesus’s listeners (

We might well miss the social tensions invoked in reading the parable of the Good Samaritan (

Parables, like all other passages of Scripture, need to be interpreted within the context of Scripture as a whole. They are not intended to be stand-alone stories. Just like we would miss the meaning of a movie by only watching one scene, we will more than likely misinterpret Scripture if we isolate specific sets of verses from the passages, chapters, and books surrounding it. Where an interpretation contradicts or strays from another passage, it needs to be reined in and adjusted.

For example, John Piper writes that if the parable of the vineyard workers in

In other passages, the immediate context proves helpful. The parable of the unforgiving servant teaches us about the magnitude of God’s forgiveness (

The call to grow in knowledge and understanding of our Lord and Savior is a life-long endeavor (

Photo credit: Getty Images/wynnter

With a heart for teaching, Madison Hetzler is passionate about edifying fellow believers to be strong, confident, and knowledgeable in the Word of God. Madison graduated from Liberty University's School of Divinity and now instructs Bible courses for Grace Christian University. She leads weekly studies in her church and home, cherishing any opportunity to gather with others around God’s Word.

Originally published October 21, 2019.