What Is the Masoretic Text?

I haven’t always been a Bible nerd. I remember the first 500-page theology book I read in college. The first few pages are filled with words circled, question marks, and definitions in the margin. I didn’t understand half of the words. How am I supposed to know what a “hermeneutical morass” is?

When I first preached through a book of the Old Testament (as a youth pastor in a small town) I found myself consulting commentaries for help. By this time, I understand more of the words, but I also kept seeing certain abbreviations used, of which I was still clueless. What is the LXX? What is the MT?

After a bit more schooling, I became very familiar with the LXX. What is that? It is an abbreviation for the Septuagint. And that is the Greek translation of the Old Testament. It would have likely been the Bible which both Jesus and Paul were most familiar. The LXX is the Roman numeral 70, and that is used as an abbreviation because that’s what Septuagint means—The Translation of the Seventy. 70 scholars translated the Hebrew OT into the Greek language of the day.

But there was another abbreviation which it took me a bit longer to understand--MT. I knew that was the abbreviation for Montana, but I assumed that wasn’t what the commentators were referencing. I learned that it is the abbreviation for the Masoretic Text. What in the world is that?

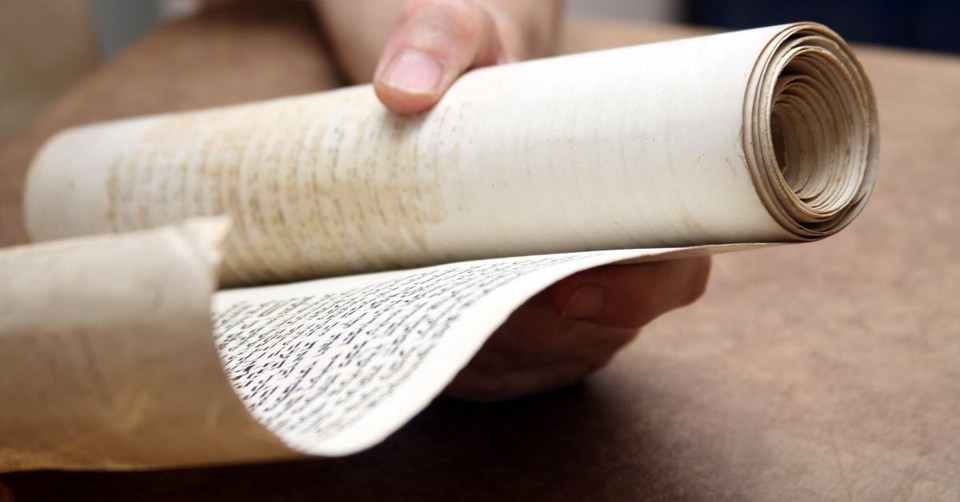

What Is the Masoretic Text?

The Masoretic Text is considered by most to be the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the Hebrew Bible. It is this text which is the basis for most English translations of the Old Testament.

The LXX is the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, and it was written around the middle of the 3rd century BC (a couple hundred years before Jesus). How old, then, do you expect the Masoretic Text to be? I would expect it to be much older—maybe sometime before the Babylonian exile of 586 BC. But that’s not the case at all. The LXX is actually around 1,000 years older than the Masoretic Text.

But that’s not entirely accurate. Jewish copyists had been preserving the Old Testament for centuries. We read in 1 Chronicles 2:55 of some of these professional scribes. They were meticulous in their copying and counting of letters. They devoted their lives to making sure that every single syllable of the text remained pure.

But part of what was being preserved was the “oral Torah.” It was this that was handed down from God, to Moses, and then to the Israelites. This is what was supposed to be written on their hearts. When the second temple was destroyed, they began working to preserve this oral tradition.

There is some difficulty here, though. The original Hebrew had no vowels and no punctuation. It was meant to be spoken and not read. After many years, and an exile, nobody spoke or read ancient Hebrew anymore. So, how could they make it readable and understandable again?

In his book, How We Got the Bible, Timothy Paul Jones, gives a helpful illustration.

Today, if we tried to write right-to-left with no obvious vowels and no lower-case letters in the English language, one familiar sentence from Scripture would end up looking something like this:

‘N’ S’ DR’L ‘HT D’G R” DR’L ‘HT L’RS’ ‘ R’H (pg. 39)

That looks more like a strong password that your iPhone might suggest, than a popular Bible verse. But it’s a part of Deuteronomy 6:4. “Hear O Israel, the Lord your God the LORD is One.”

The Masoretes labored to make it more readable. They added vowel markings, accents, marginal notes to help with reading, and more. This is why it is now called the Masoretic Text. What is considered to be the received and authoritative text is that of Jacob en-chayim ibn Adonijah (good luck remembering that for a Jeopardy answer). This version was published in 1524. That means if we say something like the Masoretic Text was completed in 1524 by that Adonijah guy, we must acknowledge that this has come from years of laborious preservation.

But is it the most faithful to the original?

Is it the Most Accurate?

There are some discrepancies between the MT and the LXX (Do you know those abbreviations now?) What do we do when a New Testament writer—one who we believe to be inspired—quotes from the LXX and not the MT? What do we do with passages that are flat-out missing in the MT but are quoted in the New Testament?

Is it possible that the Masoretes, coming a few centuries after the spread of Christianity, would have deliberately left out parts of the Scriptures? Would they have done this to obscure the gospel? I suppose this is possible, but if this is the case, they did an incredibly horrible job of doing so. There are very few places where the difference has any bearing on interpretation. And even in these differences no major doctrine hinges upon the textual differences. If they wanted to throw shade on the gospel—Isaiah 53 would have been a great place to do this.

But we can be pretty certain that they did not do this because of what was discovered in 1947 amongst the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Dead Sea Scrolls, preserved in the Qumran community, give us 232 manuscripts of the Old Testament. And these scrolls are dated from around the 3rd century BC to the 1st century AD. This means they are hundreds of years older than the Masoretic Text. It’s almost unbelievable what they found. I’ll turn to Timothy Paul Jones again,

In fact, a scroll of Isaiah found among the Dead Sea Scrolls was copied more than a hundred years before Jesus was born; yet, the wording of this scroll of Isaiah agreed almost completely with Masoretic texts that were copied a thousand years later! (pg. 43-44)

What does this mean? It means that the Masoretic text is incredibly accurate. It’s safe to say, then, that the LXX is accurate enough that God found it acceptable to quote through New Testament authors. And we can say that the MT is also a faithful preservation of the Old Testament. All of this means that you can trust your Bible.

Photo Credit: ©GettyImages/tovfla

Mike Leake is husband to Nikki and father to Isaiah and Hannah. He is also the lead pastor at Calvary of Neosho, MO. Mike is the author of Torn to Heal and Jesus Is All You Need. His writing home is http://mikeleake.net and you can connect with him on Twitter @mikeleake. Mike has a new writing project at Proverbs4Today.

Originally published March 24, 2023.