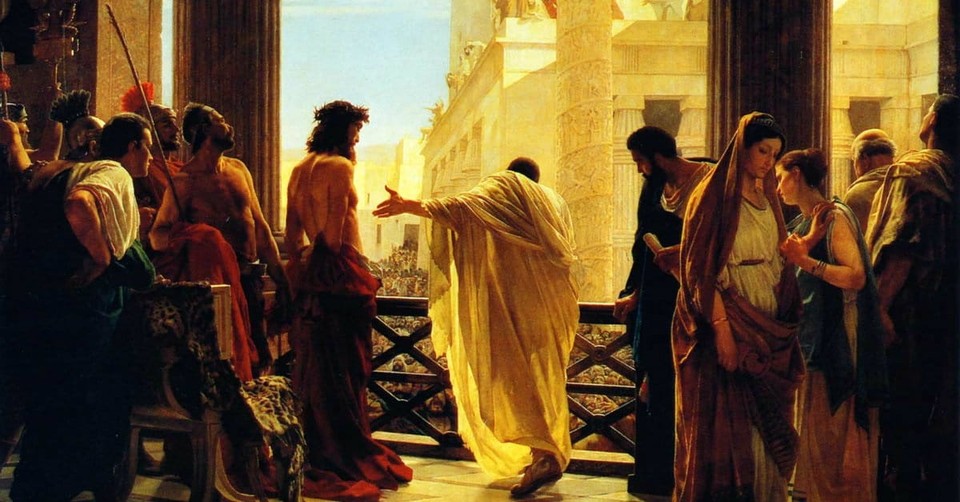

Who Killed Jesus: The Historical Context of Jesus’ Crucifixion

Much of the scholarly discussion about the circumstances of Jesus’ death relates to the question of who was responsible for his arrest and crucifixion.

Who killed Jesus? The Jews or the Romans?

Historically, the primary responsibility has been placed on the Jewish leadership and the Jews in Jerusalem. Throughout the centuries, this has sometimes had tragic consequences, resulting in anti-Semitism and violence against Jews.

More recent trends in scholarship have shifted the blame to the Romans.

The tendency to blame the Jews, it is said, arose in the decades after the crucifixion with the church’s growing conflict with the synagogue and its desire to convince Rome that Christianity was no threat to the empire.

Most contemporary scholars recognize that there is not an either-or solution to this question, but that both Jewish and Roman authorities must have played some role in Jesus’ death.

First, Jesus was crucified—a Roman rather than a Jewish means of execution. (Stoning was the more common Jewish method.) There is good evidence that at this time the Jewish Sanhedrin did not have authority to carry out capital punishment (John 18:31; y. Sanh. 1:1; 7:2). The Roman governor Pontius Pilate no doubt gave the orders for Jesus’ crucifixion, and Roman soldiers carried it out.

At the same time, all that we know about Jesus’ teachings and actions suggest that he was more apt to offend and provoke the Jewish religious leaders than the Roman authorities. It is unlikely that the Romans would have initiated action against him without prompting from the Jewish authorities.

So was Jesus crucified for political reasons or for religious reasons?

Raising the question this way actually misrepresents first-century Judaism, in which religion and politics were inseparable. Jesus’ death was no doubt motivated by the perceived threat felt by the religious-political powers of his day.

Let’s take a look at the motivations, tendencies, and actions of these authorities.

The motivations of Pilate and the Romans

The evidence points to the conclusion that Jesus was executed by the Romans for sedition—rebellion against the government.

1. First, he was crucified as “king of the Jews.” As noted in the last unit, the titulus on the cross announcing this is almost certainly historical.

2. Second, he was crucified between two “robbers” or “criminals”—Roman terms used of insurrectionists (Mark 15:27; Matt. 27:38; Luke 23:33; John 19:18). Another insurrectionist, Barabbas, was released in his place (Mark 15:7; Matt. 27:16; Luke 23:19; John 18:40).

3. Finally, the account of charges brought to Pilate by the Sanhedrin in Luke’s Gospel is related to sedition: “And they began to accuse him, saying, ‘We have found this man subverting our nation. He opposes payment of taxes to Caesar and claims to be Christ, a king. . . . He stirs up the people all over Judea by his teaching. He started in Galilee and has come all the way here’ ” (Luke 23:2, 5).

While this evidence confirms the charge against Jesus, it raises the mystifying question of why Jesus was crucified, since he had almost nothing in common with other rebels and insurrectionists of his day. He advocated love for enemies and commanded his followers to respond to persecution with acts of kindness (Matt. 5:38–48; Luke 6:27–36). He affirmed the legitimacy of paying taxes to Caesar (Mark 12:14, 17; Matt. 22:17, 21; Luke 20:22, 25). At his arrest, he ordered his disciples not to fight but to put away their swords (Matt. 26:52; Luke 22:49–51). His few enigmatic sayings about taking up the sword probably carry spiritual rather than military significance (Matt. 10:34; Luke 22:36, 38).

Jesus’ kingdom preaching would hardly be viewed by Pilate as instigating a military coup.

Furthermore, the fact that Jesus’ followers were not rounded up and executed after his death, and were even allowed to form a faith community in Jerusalem, confirms that Jesus was not viewed as inciting a violent insurrection. The early church was surely following the teaching of its master when it advocated a life of love, unity, and self-sacrifice (Acts 2:42–47; 4:32–35).

Why did Pilate have Jesus crucified?

While it is unlikely that Pilate viewed Jesus as a significant threat, he also had little interest in justice or compassion.

We know from other sources that Pilate’s governorship was characterized by a general disdain toward his Jewish subjects and brutal suppression of opposition. At the same time, his support from Rome was shaky at best, and he feared to antagonize the Jewish leadership lest they complain to the emperor. Pilate had originally been appointed the governor of Judea in AD 26 by Sejanus, an advisor to Emperor Tiberius. When Sejanus was caught conspiring against Tiberius and was executed in AD 31, Pilate too came under suspicion. Pilate’s tenuous position is well illustrated by the Jewish philosopher Philo, who writes about an incident when the Jews protested against Pilate’s actions in placing golden shields in Herod’s palace in Jerusalem:

He feared that if they actually sent an embassy [to Rome] they would also expose the rest of his conduct as governor by stating in full the briberies, the insults, the robberies, the outrages and wanton injustices, the executions without trial constantly repeated, the ceaseless and supremely grievous cruelty. So with all his vindictiveness and furious temper, he was in a difficult position.*

While Philo may be exaggerating Pilate’s faults, the picture here is remarkably similar to that of the Gospels—an unscrupulous and self-seeking leader who loathed the Jewish leadership but feared to antagonize them.

When the Jewish leaders warn Pilate, “If you let this man go, you are no friend of Caesar” (John 19:12), he would surely have felt both anger and fear.

Most likely, Pilate ordered Jesus’ execution for three reasons:

1. It placated the Jewish leaders and so headed off accusations against him to Rome.

2. It preemptively eliminated any threat Jesus might pose if the people actually tried to make him a king.

3. It ruthlessly warned other would-be prophets and messiahs that Rome would stand for no dissent.

Jewish opposition to Jesus

During Jesus’ Galilean ministry, he faced opposition primarily from the Pharisees and their scribes.

In his last week in Jerusalem, the opposition came especially from the priestly leadership under the authority of the high priest and the Sanhedrin, which was dominated by the Sadducees.

Torah (the law) and temple were the two great institutions of Judaism. Jesus apparently challenged the authority and continuing validity of both, posing a significant threat to Israel’s leadership.

Why the Pharisees opposed Jesus

The opposition Jesus faced from the Pharisees and scribes centered especially on his teaching and actions relating to the law and the Sabbath. He claimed authority over the law, treated the Sabbath command as secondary to human needs, and accused the Pharisees of elevating their oral law—mere human traditions—over the commands of God. He also accused them of pride, hypocrisy, and greed, warning the people to do as they say but not as they do (Matt. 23:3). These actions certainly did not win him friends among the religious leaders.

Jesus’ proclamation of the kingdom of God and his calling of twelve disciples would have also provoked anger among the Pharisees, who considered themselves the rightful guardians of Israel’s traditions.

Jesus’ call for them to repent, his warning of coming judgment, and his actions in creating a new community of faith all sent the message that Israel needed restoration and that her leaders were illegitimate and corrupt. In the boiling cauldron of religion and politics that was first-century Palestine, Jesus’ words would have provoked strong opposition.

Why the Sadducees opposed Jesus

While Jesus certainly made enemies before his final journey to Jerusalem, it was the events of the final week which resulted in his crucifixion.

In fact, Jesus’ clearing of the temple is widely recognized as the key episode which provoked the Jewish authorities to act against him. His attacks were aimed at the Sadducees, who represented the religious leadership of Jerusalem.

Here’s what happened: in Mark’s account of Jesus’ Jewish trial, “false witnesses” are brought forward who testify, “We heard him say, ‘I will destroy this man-made temple and in three days will build another, not made by man.’ ” The high priest then questions him, “Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed One?” to which Jesus’ replies, “I am . . . and you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Mighty One and coming on the clouds of heaven.” The high priest responds with rage and accuses Jesus of blasphemy. The whole assembly calls for his death (Mark 14:58–65; cf. Matt. 26:55–68; Luke 22:66–71).

Questioning the historicity of Jesus’ trial

Some have questioned the historicity of this scene, claiming it violates Jewish trial procedures. For example, the Mishnah states that it is illegal for the Sanhedrin to meet at night, on the eve of Passover, or in the high priest’s home.

A second hearing would also have been necessary for a death sentence, and a charge of blasphemy could be sustained only if Jesus had uttered the divine name of God (m. Sanh. 4:1; 5:5; 7:5; 11:2).

This argument is not decisive for four reasons:

1. First, the procedures set out in the Mishnah were codified in AD 200 and may not all go back to the time of Jesus.

2. Second, even if they do go back to the first century, they represent an ideal situation which may or may not have been followed in Jesus’ case. The existence of guidelines suggests abuses in the past. They may have arisen as correctives to illegitimate trials like this one.

3. Third, the Mishnah represents predominantly Pharisaic traditions, but the Sadducees were dominant in the Sanhedrin of Jesus’ day.

4. Finally, there is good evidence that blasphemy was sometimes used in Judaism in a broader sense than uttering the divine name, including actions like idolatry, arrogant disrespect for God, or insulting his chosen leaders.

On closer inspection, Mark’s trial account makes good sense when viewed in the context of Jesus’ ministry.

Jesus’ temple action would naturally have prompted the high priest to ask if he was making a messianic claim.

Jesus’ response combines two key Old Testament passages, Psalm 110:1 and Daniel 7:13. The first indicates that Jesus will be vindicated by God and exalted to a position at his right hand. The latter suggests Jesus will receive sovereign authority to judge the enemies of God.

By combining these verses, Jesus asserts that the Sanhedrin is acting against the Lord’s anointed, that they will face judgment for this, and that Jesus himself will be their judge!

Such an outrageous claim was blasphemous to the body, which viewed itself as God’s appointed leadership, the guardians of his holy temple. Jesus was challenging not only their actions but also their authority and legitimacy. Such a challenge demanded a response.

What a rebellion would mean

There were also political and social consequences to consider. Jesus’ actions in the temple—probably viewed by the Sanhedrin as an act of sacrilege—together with his popularity among the people, made it imperative to act against him quickly and decisively.

A disturbance of the peace might bring Roman retribution and disaster to the nation and its leaders. The earlier words of the Pharisees and chief priests in John are plausible in this scenario: “If we let him go on like this, everyone will believe in him, and then the Romans will come and take away both our place and our nation” (John 11:48).

The Sanhedrin, therefore, turned Jesus over to Pilate, modifying their religious charges to political ones—sedition and claiming to be a king in opposition to Caesar—and gaining from Pilate a capital sentence.

*See Philo, Legum allegoriae 302f. (Colson, LCL). Pilate was eventually recalled to Rome in AD 36 after a typically ruthless military action against the Samaritans (Josephus, Ant. 18.4.2 §§85–87).

This post is adapted from material found in the Four Portraits, One Jesus online course, taught by Mark Strauss. Originally published on ZondervanAcademic.com. Used with permission.

Mark Strauss (Ph.D., Aberdeen) is a professor of New Testament at Bethel Seminary in San Diego. He has written The Davidic Messiah in Luke-Acts, Distorting Scripture?: The Challenge of Bible Translation and Gender Accuracy, Luke in the Zondervan Illustrated Bible Background Commentary series, and Mark in the Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament.

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons Images by Antonio Ciseri

Publication date: April 21, 2017

Originally published April 21, 2017.