Who Wrote the Book of Hebrews?

When you consider the wide agreement among biblical scholars about who wrote every other book of the New Testament, it’s a little mysterious that we don’t know who wrote Hebrews.

There are a handful of contenders. Let’s take a look at the reasons each of them might be the author.

Did Paul write Hebrews?

It is possible Paul wrote the book of Hebrews. There are a couple reasons why this might be the case.

First, in the earliest manuscript editions of the New Testament books, Hebrews is included after Romans among the books written by the apostle Paul. This was taken as evidence that Paul had written it, and some Eastern churches accepted Hebrews as canonical earlier than in the West.

Second, both Clement of Alexandria (c. AD 150 – 215) and Origen (AD 185 – 253) claimed a Pauline association for the book but recognized that Paul himself probably did not put pen to paper for this book, even though they did not know the author’s name.

Clement of Alexandria suggests that Paul wrote the book originally in Hebrew and that Luke translated it into Greek, though the Greek of Hebrews bears no resemblance to translation Greek (e.g., that of the Septuagint).

The King James Version assumes Pauline authorship

The nuanced position on the authorship question by the Alexandrian fathers was obscured by later church tradition that mistook Pauline association for Pauline authorship.

The enormously influential King James Bible took its cue from this tradition. In fact, in the KJV, you’ll find the title translated as it was found in some manuscripts: “The Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Hebrews.” The tradition of Pauline authorship continued.

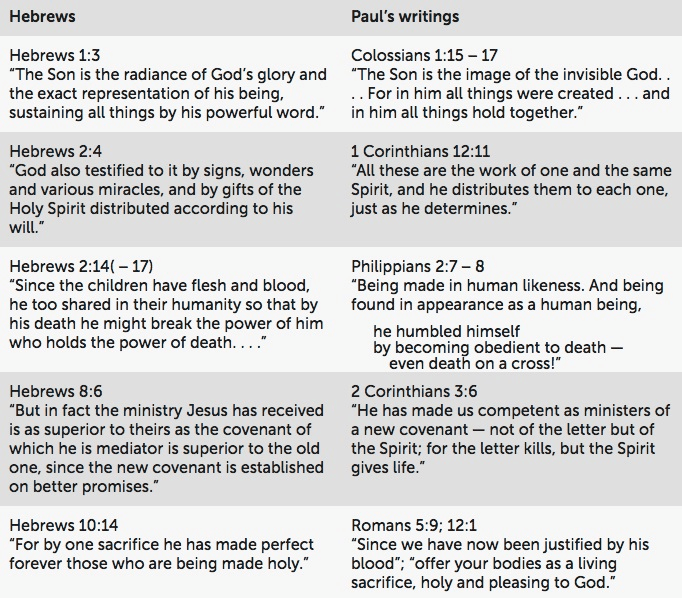

Parallels between Hebrews and Paul’s writings

It’s certainly reasonable to conclude Paul wrote the book of Hebrews. Many of the thoughts of Hebrews are similar to those found in Paul’s writings:

The soteriology of Hebrews is quite consistent with Paul’s own teaching. For instance, the statement in Hebrews 10:14 that those who have been “made perfect” are in the process of being “made holy” sounds very much like Paul’s teaching on justification (e.g., Rom. 3:21 -5:9) and sanctification (e.g., Rom. 8:1-17). Moreover, both Paul and the author of Hebrews thought of Abraham as the spiritual father of Christians in similar ways.

Reasons Paul did not write Hebrews

In spite of all this evidence for Pauline authorship, few New Testament scholars today believe Paul wrote it.

Both John Calvin and Martin Luther shared this judgment as far as the sixteenth century.

Even centuries earlier in the fourth century, the church of Rome did not believe Paul wrote Hebrews, possibly retaining a latent memory of the actual author (Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 3.3.5; 6.20.3).

In other words, the rejection of Pauline authorship of Hebrews is a long-standing position in the church.

What can we infer from the book of Hebrews itself?

The internal evidence presented by the book of Hebrews itself indicates an author other than Paul.

- The style of Hebrews, except in the closing verses (13:18 -25), is quite unlike any other writing of Paul’s that has survived.

- In keeping with the style of a person well educated in formal rhetoric, the Greek of Hebrews is highly literary and very ornate.

- The vocabulary is sophisticated, and it includes 150 words that are not found elsewhere in the New Testament and 10 that do not occur in any other Greek writings that have survived for our study.

- The structure of the epistle conforms to conventions found in Greek rhetoric used when a speech was designed to persuade its audience to action. Much of this rhetorical achievement is lost when the original Greek of Hebrews is translated into modern language, but in the original it is elegant and euphonious Greek prose. The high rhetorical quality of Hebrews indicates that its author most likely had the most advanced literary education of any of the New Testament writers.

- The author does not introduce himself as Paul typically did (cf. 2 Cor. 1:1; Gal 1:1; Eph. 1:1; Col. 1:1; 1 Tim. 1:1; and 2 Tim. 1:1).

- Its theology, though very compatible with that of the Pauline letters, is very distinctive. The apostle Paul, for instance, never alludes to Jesus as a priest, which is the major motif of Hebrews. In fact, Hebrews is the only New Testament writing to expound on Jesus as the Great High Priest and final sacrifice.

The most persuasive argument against Pauline authorship

An even more persuasive argument that the apostle Paul was not the author of Hebrews is the way the author alludes to himself in Hebrews 2:3, stating that the gospel was confirmed “to us” by those who heard the Lord announce salvation.

The apostle Paul always made the point that, even though he wasn’t one of the twelve original disciples who walked with Jesus during his earthly life, he was nonetheless an apostle of Jesus Christ, and usually identifies himself as such in his letters. It seems unlikely that Paul here in 2:3 would refer to himself as simply someone who received the gospel from those who had heard the Lord.

If not Paul, then who are the other possible authors?

We’ve established that someone other than Paul wrote the epistle.

But it is possible—even likely—that because of some of the parallels with Paul’s epistles, we know the following things about the author:

- The author was likely a close associate of Paul

- The author was able to write in a rhetorically ornate Greek style

- The author had become a Christian out of Judaism

- The author’s understanding of the doctrine of salvation was highly compatible with what the apostle Paul taught, though creatively distinctive.

Connection to Alexandria

Christianity reached Alexandria at a very early date. The missionary impetus of the Christian gospel arose in Jerusalem following the stoning of Stephen when a great persecution broke out and Christians began to scatter (Acts 8).

When Acts 6:1 mentions both Hellenistic and Hebraic Jews, the phrase pros tous hebraious is used in that context, the exact phrase by which Hebrews is later known. One twentieth-century scholar named William Manson suggested that Christians who were of the same mind as Stephen brought the Christian message to Alexandria, noting several elements common to Stephen’s speech in Acts 7 that are also shared by the book of Hebrews.

- its high rhetorical style,

- its use of the Septuagint, and

- its possible conceptual constructs

These connections make it very likely that the author was originally from the Alexandrian church, regardless of where he was when he penned the letter, and regardless of to whom it was originally sent.

Because of this, a possible author is Apollos, a native of Alexandria, according to Acts 18:24.

Why Apollos might have been the author of Hebrews

Here’s what we know about Apollos from the Bible:

- He was from Alexandria and traveled in the Apostle Paul’s orbit (Acts 18:24).

- He was taught by Paul’s companions, Priscilla and Aquila (Acts 18:24 -28),

- Paul knew Apollos personally, and encouraged him in his ministry (1 Cor. 16:12).

- He was a highly educated Alexandrian who would have been schooled in the literary style exemplified by Hebrews.

- Moreover, as a Jewish believer (Acts 18:24), he had the thorough knowledge of the Old Testament Scriptures in their Greek version that the book of Hebrews exclusively uses.

- Apollos was a great defender of the Christian faith, vigorously refuting the opposing Jews in public debate and proving from the Old Testament that Jesus was the Messiah (Acts 18:28).

- He eventually became as influential as the apostles Paul and Peter (1 Cor. 1:12; 3:4 – 6, 22; 4:6; 16:12).

We also know from the very early history of the church that Apollos would also fit the memory handed down to both Clement of Alexandria (c. AD 150 – 215) and to Origen (AD 185 – 253), who claimed a Pauline association. Origin also recognized that Paul himself probably did not write Hebrews.[5]

For these reasons, Apollos of Alexandria has been a leading contender for the authorship of Hebrews at least as far back as the great Protestant Reformer, Martin Luther, but he has not been the only contender.

Clement

Eusebius, the great historian of the church, recognizes that the letter Clement wrote from Rome to the Corinthian church in the late first century contained many allusions to and quotations from Hebrews and notes that on that basis some believed that Clement himself was the translator or author of Hebrews (Hist. eccl. 3.38.2).

However, scholarly examination shows that the Greek text of Hebrews could not be a translation of a Semitic text — at least as we understand “translation” today — because its rhetorical features would be possible only when composed in Greek.

And so if either Clement or Luke were involved in the production of the extant book of Hebrews, he would have had a very free hand in working with Paul’s material, to the point that he would be an author, not a translator by any modern definition.

Barnabas

The church father Tertullian (AD 160? – 220?) mentioned that Barnabas, Paul’s traveling companion on his first mission to the Gentiles, authored Hebrews (Pud. 20). The association of Barnabas with the book of Hebrews may be because he was described as a “son of encouragement” (Acts 4:36), and Hebrews 13:22 describes the letter as a word of encouragement (or exhortation). Moreover, Barnabas is referred to as an “apostle” (Acts 14:14) and, being a Levite (Acts 4:36), would have had the interest in and knowledge about the priesthood that forms such a dominant theme in Hebrews.

Timothy

A recent theory suggests that Timothy wrote Hebrews, except for the closing verses that Paul appended himself where Timothy is mentioned by name.[6]

While Timothy was a close associate of Paul, he was from Lystra, a small town in Asia Minor where it is unlikely he could have received the formal rhetorical training reflected in Hebrews.

Furthermore, it is doubtful that Timothy had any connection to Alexandria, though that connection may not be necessary. What we know of Apollos matches more closely what we see in Hebrews than does what we know of Timothy.

Priscilla

The intriguing theory presented in more modern times by the German biblical scholar Adolf Harnack argued that Hebrews was written by Priscilla, the woman who, together with her husband, Aquila, was a close associate of Paul’s.

Although Harnack’s idea generated much discussion in its day, the author refers to himself in Hebrews 11:32, using a masculine participle in the Greek original, and there is no manuscript evidence for a feminine variant reading.

Harnack’s argument that Priscilla deliberately disguised her gender by using the masculine gender is sheer speculation, and his theory remains a curiosity of New Testament scholarship.

So who really wrote the book of Hebrews?

Clement? Paul? Luke? Timothy? Barnabas? Apollos? In spite of the weight of scholarly inference, the book of Hebrews does not in fact name its author. And so if you were ever asked about the authorship of Hebrews, the correct answer is well expressed by the church father Origen (AD 185? – 254?), who said, according to Eusebius, “Who wrote the epistle of Hebrews? In truth, only God knows!” (Hist. eccl. 6.25.14).

This article originally appeared on ZondervanAcademic.com. Used with permission.

Image courtesy: ©Thinkstock/aradaphotography

Publication date: April 26, 2017

Originally published April 26, 2017.