12 Principles for Disagreeing with Other Christians

This post is adapted from Conscience: What It Is, How to Train It, and Loving Those Who Differ by Andrew David Naselli and J. D. Crowley.

1. Welcome those who disagree with you (Rom. 14:1–2).

Concerning any area of disagreement on third-level matters [i.e., disputable issues that shouldn’t cause disunity in the church family], a church will have two groups: (1) those who are “weak in faith” (14:1) on that issue and (2) those “who are strong” (15:1). The weak in faith have a weak conscience on that matter, and the strong in faith, a strong conscience.

Don’t forget that “faith” here refers not to saving faith in Christ (14:22a makes that clear) but to the confidence a person has in their heart or conscience to do a particular activity, such as eat meat (14:2). The weak person’s conscience lacks sufficient confidence (i.e., faith) to do a particular act without self-judgment, even if that act is actually not a sin. To him it would be a sin.

What this means is that you are responsible to obey both Paul’s exhortations to the weak and his exhortations to the strong, since (1) there are usually people on either side of you on any given issue and (2) you yourself likely have a stronger conscience on some issues and a weaker conscience on others. This brings us to Paul’s second principle when Christians disagree on scruples.

2. Those who have freedom of conscience must not look down on those who don’t (Rom. 14:3–4).

The strong, who have freedom to do what others cannot do, are tempted to look down on and despise those who are more strict. They may say, “Those people don’t understand the freedom we have in Christ. They’re not mature like us! They’re legalistic. All they think about are rules.” Paul condemns this attitude of superiority.

3. Those whose conscience restricts them must not be judgmental toward those who have freedom (Rom. 14:3–4)

Those who have a weaker conscience on a particular issue are always tempted to pass judgment on those who are freer. They may say, “How can those people be Christians and do that? Don’t they know they’re hurting the testimony of Christ? Don’t they know that they are supposed to give up things like that for the sake of the gospel?”

Paul gives two reasons that it’s such a serious sin to break these two principles, that is, for the strong to look down on those with a weaker conscience and for the weak to judge those with a stronger conscience:

1. “God has welcomed him” (14:3c). Do you have the right to reject someone whom God has welcomed? Are you holier than God? If God himself allows his people to hold different opinions on third-level matters, should you force everyone to agree with you?

2. “Who are you to pass judgment on the servant of another?” (14:4a). You are not the master of other believers. When you look down on someone with a weaker conscience or judge someone with a stronger conscience, you’re acting as though that person is your servant and you are his master. But God is his master. In matters of opinion, you must let God do his work. You just need to welcome your brother or sister. God is a better master than you are.

4. Each believer must be fully convinced of their position in their own conscience (Rom. 14:5).

Should Christians celebrate Jewish holy days? This issue, which Paul is addressing here, illustrates the principle that on disputable matters, you should obey your conscience.

This does not mean that your conscience is always right. It’s wise to calibrate your conscience to better fit God’s wil. But it does mean that you cannot constantly sin against your conscience and be a healthy Christian. You must be fully convinced of your present position on food or drink or special days—or whatever the issue—and then live consistently by that decision until God may lead you by his Word and Spirit to adjust your conscience.

5. Assume that others are partaking or refraining for the glory of God (Rom. 14:6–9).

Notice how generous Paul is to both sides. He assumes that both sides are exercising their freedoms or restrictions for the glory of God. Wouldn’t it be amazing to be in a church where everyone gave each other the benefit of the doubt on these differences, instead of putting the worst possible spin on everything?

Paul says that both the weak and the strong can please the Lord even while holding different views on disputable matters. They have different positions but the same motivation: to honor God.

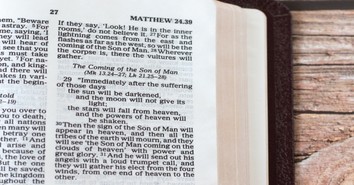

6. Do not judge each other in these matters because we will all someday stand before the judgment seat of God (Rom. 14:10–12).

If we thought more about our own situation before the judgment throne of God, we would be less likely to pass judgment on fellow Christians. On that day we’ll be busy enough answering for our own life; we don’t need to spend our short life meddling in the lives of others. In these matters where good Christians disagree, we just need to mind our own conscience and let God be the judge of others.

7. Your freedom to eat meat is correct, but don’t let your freedom destroy the faith of a weak brother (Rom. 14:13–15).

Free and strict Christians in a church both have responsibilities toward each other. Strict Christians have a responsibility not to impose their conscience on everyone else in the church. It is a serious sin to try to bind someone else’s conscience with rules that God does not clearly command.

But the second half of Romans 14 places the bulk of responsibility on Christians with a strong conscience. One obvious reason is that they are strong, so God calls on them to bear with the weaknesses of the weak (Rom. 15:1). Not only that, of the two groups, only the strong have a choice in third-level matters like meat, holy days, and wine. They can either partake or abstain, whereas the conscience of the strict allows them only one choice. It is a great privilege for the strong to have double the choices of the weak. They must use this gift wisely by considering how their actions affect the sensitive consciences of their brothers and sisters.

8. Disagreements about eating and drinking are not important in the kingdom of God; building each other up in righteousness, peace, and joy is the important thing (Rom. 14:16–21).

The New Testament clearly and repeatedly lays down the principle that God is completely indifferent to what we ingest. First and most important, the Lord Jesus himself memorably proclaimed all foods to be legitimate for eating in Mark 7:1–23 (esp. vv. 18–19). Since Peter didn’t seem to get the memo, the Lord Jesus had to give him a vision three times to show him that Christians must not make food an issue (Acts 10:9–16). Then in 1 Corinthians 8:8, Paul comes right out and says it: “Food will not commend us to God. We are no worse off if we do not eat, and no better off if we do.” And just in case we still didn’t get it, God gave us Romans 14:17, which shows that the kingdom of God has nothing to do with food and drink. Nothing. God doesn’t care at all about what we ingest.

This might seem mistaken. Doesn’t God care if we take poison? Not if the purpose is to cure. Every day Christians take poison into their bodies to cure themselves of cancer. But if we take in poison to kill ourselves, that’s another matter entirely. In Christianity, why you do things is more important than what you do.

9. If you have freedom, don’t flaunt it; if you are strict, don’t expect others to be strict like you (Rom. 14:22a).

This truth applies equally to the strong and the weak. To those with a strong conscience you have much freedom in Christ. But don’t flaunt it or show it off in a way that may cause others to sin. Be especially careful to nurture the faith of young people and new Christians.

Those of you with a weak conscience in a particular area also have a responsibility not to “police” others by pressuring them to adopt your strict standards. You should keep these matters between yourself and God.

10. A person who lives according to their conscience is blessed (Rom. 14:22b–23).

God gave us the gift of conscience in order to significantly increase our joy as we obey its warnings. One of the two great principles of conscience is to obey it. Just as God’s gift of touch and pain guards us from what would rob us of physical health, conscience continually guards us from the sin that robs our joy.

11. We must follow the example of Christ, who put others first (Rom. 15:1–6).

This principle doesn’t mean that the strong have to agree with the position of the weak. It doesn’t even mean that the strong can never again exercise their freedoms. On the other hand, neither does it mean that the strong only put up with or endure or tolerate the weak, like a person who tolerates someone who annoys him. For a Christian, to “bear with” the weaknesses of the weak means that you gladly help the weak by refraining from doing anything that would hurt their faith.

Romans 15:3 emphasizes the example of Christ. We cannot even begin to imagine the freedoms and privileges that belonged to the Son of God in heaven. To be God is to be completely free. Yet Christ “did not please himself” but gave up his rights and freedoms to become a servant so that we could be saved from wrath. Compared to what Christ suffered on the cross, to give up a freedom like eating meat is a trifle indeed.

12. We bring glory to God when we welcome one another as Christ has welcomed us (Rom. 15:7).

With this sentence, Paul bookends this long section that began with similar words in 14:1: “Welcome him. . . .” But here in 15:7 Paul adds a comparison—“as Christ has welcomed you”—and a purpose—“for the glory of God.” It matters how you treat those who disagree with you on disputable matters. When you welcome them as Christ has welcomed you, you glorify God.

[Editor’s Note: Content taken from Conscience: What It Is, How to Train It, and Loving Those Who Differ by Andrew David Naselli and J. D. Crowley, originally appearing on Crossway's blog, ©2016. Used by permission of Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers, Wheaton, Il 60187.]

Andrew David Naselli (PhD, Bob Jones University; PhD, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School) is assistant professor of New Testament and biblical theology at Bethlehem College & Seminary in Minneapolis, Minnesota

J. D. Crowley (MA, Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary) has been doing missionary and linguistic work among the indigenous minorities of northeast Cambodia since 1994. He is the author of numerous books, including Commentary on Romans for Cambodia and Asia and the Tampuan/Khmer/English Dictionary.

Publication date: April 29, 2016

Originally published April 29, 2016.