Proverbs 31 Woman on Steroids

She selects wool and flax and works with eager hands.

She is like the merchant ships, bringing her food from afar.

She gets up while it is still night; she provides food for her family. . . .

She considers a field and buys it; out of her earnings she plants a vineyard.

She sets about her work vigorously; her arms are strong for her tasks

She sees that her trading is profitable, and her lamp does not go out at night.

Proverbs 31:14-18

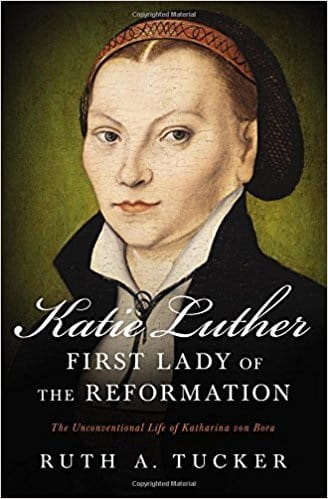

Katharina von Bora, Wife of Martin Luther

Mothers’ Day in decades gone by. How well I remember the frequent sermons on the Proverbs 31 woman. Husbands nodded their heads in agreement, while wives sat tense in the pew, convinced the writer of the book was setting forth an impossible standard designed for Mothers’ Day sermons for millennia to come. But then somewhere in the 1990s, preachers became more gender conscious, and began suggesting that this woman was a composite. Solomon, or whoever authored the passage, was thinking of the good traits of all women and squeezing them into just one wife. No woman could in real life, 24/7, be so efficient.

I beg to differ. There is a woman who is the Proverbs 31 and more. I had never before imagined the possibility, having studied women in history—even very modern history—and never come across such a creature. Then I began writing a biography of Katharina von Bora, the wife of Martin Luther. The biggest difference between her and the biblical woman, is that the latter is the subject of the text. In the sixteenth-century story, Martin is the larger than life character, and his wife Katie typically plays little more than a bit part. Here, however, as in the biography, Katie is the star—the morning star, as she was identified by her husband because of her early rising. And we will see her out-shining even the Proverbs 31 woman.

I have known Katie superficially for decades, and even now wonder if I actually know who this sixteenth-century woman was—besides the fact that she was a workaholic. So was Martin. Even before he nailed his ninety-five theses to the Castle Church door in Wittenberg in 1517, he had spent his days teaching and writing and fulfilling all the other duties required of a monk. He workload was no lighter after he left the monastery and after he married Katie. But we often see Martin spending time just chewing the fat with colleagues, singing and playing the lute, or on the floor playing with children. But Katie took no time for relaxation—at least after marriage and motherhood consumed her life.

From the age of five until she escaped in her early twenties, Katie was cloistered in a convent, her life strictly regulated by specified hours of religious ritual, education and work. Her daring escape with eleven other nuns was the capstone of one of the most astonishing conspiracies of the sixteenth century. Imagine a dozen captive women, having taken vows of silence, communicating with each other and with individuals outside the convent. Somehow it all came together. The horse-drawn wagon bringing in herring barrels exited with twelve nuns—a capital crime carried out in the dark of night.

Katie was what Catholics call a religious—a nun or a monk who has taken religious vows and lives in community. Within a matter of hours she went from religious to secular. There was no in-between, no role as part-time or even full-time nun living outside the community. For two years she lived in limbo residing in Wittenberg, the town made famous by Luther and his 95-theses. The other eleven nuns returned to their families or married. For Katie neither was an option—that is until she fell in love with the man of her dreams. They met secretly and promises were made. But then Jerome, a university student, returned home to his well-heeled family. They were up in arms. Their son marrying an impoverished runaway nun? Despite her pleading letters, Jerome never contacted her again.

Her marriage to Luther was anything but a romance, and Luther was hardly a catch. He was sixteen years older than she, in poor health, and admitted that his bed (which he hadn’t changed in a year) was foul with sweat and stench.

So here begins the Proverbs 31 woman on steroids. Re-read the passage. In many ways it almost seems artificially clean. There’s not a word about the labor involved in fashioning a new straw tick mattress for the smelly groom. Where do we see the pain in childbearing and the anguished grief over the death of a toddler and teenager? Where are the dirty diapers, the deadbeat boarders, the sharp words and sulking silences? Nor do we read in those verses about repairing and cleaning a run-down monastery and turning it into a moneymaking Holiday Inn.

The mother of six of her own children as well as orphans and extended family members, Katie ran a tight ship. Luther’s colleagues considered her domineering, and their ill will toward her was barely disguised. But where there had been no initial romance there developed a deep love one for another. Martin’s oft-quoted expressions of love are striking—though sometimes qualified: “I would not give my Katie for France and Venice together,” but then he adds, “because God has given her to me and other women have worse faults.”

She had her faults. Of course. But Katie’s devotion to her husband and family was unrivaled, most often expressed (as true with the Proverbs 31 woman) in tireless work from dawn until dusk. Along with servants, she planted and harvested from large gardens that provided meals for her extended family and paying guests. She raised cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, and poultry. She churned butter, ground meal, and purchased farms, some more than a day’s journey afar, and was often away tending the fields. She sewed clothing, preserved food for winter, nursed the sick in her own household and in the neighborhood, and on top of that was known as one of Wittenberg’s best brewers, providing beer for the household—a most valuable commodity considering the unsafe water supply.

Perhaps the best way to describe the staggering complexity of her work is as the corporate manager of farm, garden, and monastery-medical hostel that housed extended family, travelers, and a significant number of hangers-on. All this while giving birth and taking in orphans. In fact, there were at times as many as thirty students boarding at the Black Cloister, paying for their keep in varying degrees.

There’s a folk tale I remember from childhood about a farmer who insists his work is much harder than his wife’s housework. Sick of his complaining, she offers to switch. After completing all the farm work the following day, she returns to a mess. Through various mishaps, he is hanging down the chimney by a rope ready to fall into a steaming pot of porridge

Katie would have found the tale humorous, but it didn’t apply to her. Her husband was busy as the first and greatest Protestant Reformer.

Image courtesy: Pexels.com

Publication date: July 18, 2017

Originally published July 18, 2017.