Did the Early Church Fathers Think that They Were Inspired Like the Apostles?

A number of years ago, Albert Sundberg wrote a well-known article arguing that the early church fathers did not see inspiration as something that was uniquely true of canonical books.[1] Why? Because, according to Sundberg, the early Church Fathers saw their own writings as inspired. Ever since Sundberg, a number of scholars have repeated this claim, insisting that the early fathers saw nothing distinctive about the NT writings as compared to writings being produced in their own time period.

However, upon closer examination, this claim proves to be highly problematic. Let us consider several factors.

First, the early church fathers repeatedly express that the apostles had a distinctive authority that was higher and separate from their own. So, regardless of whether they viewed themselves as “inspired” in some sense, we have to acknowledge that they still viewed the inspiration/authority of the apostles as somehow different.

A few examples should help. The book of 1 Clement not only encourages its readers to “Take up the epistle of that blessed apostle, Paul,”[2] but also offers a clear reason why: “The Apostles received the Gospel for us from the Lord Jesus Christ, Jesus the Christ was sent from God. The Christ therefore is from God and the Apostles from the Christ.”[3] In addition the letter refers to the apostles as “the greatest and most righteous pillars of the Church.”[4]

Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch, also recognizes the unique role of the apostles as the mouthpiece of Christ, “The Lord did nothing apart from the Father… neither on his own nor through the apostles.”[5] Here Ignatius indicates that the apostles were a distinct historical group and the agents through which Christ worked. Thus, Ignatius goes out of his way to distinguish own authority as a bishop from the authority of the apostles, “I am not enjoining [commanding] you as Peter and Paul did. They were apostles, I am condemned.”[6]

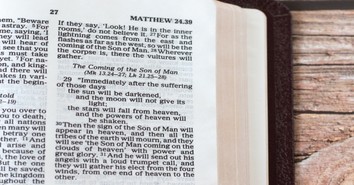

Justin Martyr displays the same appreciation for the distinct authority of the apostles, “For from Jerusalem there went out into the world, men, twelve in number… by the power of God they proclaimed to every race of men that they were sent by Christ to teach to all the word of God.”[7] Moreover, he views the gospels as the written embodiment of apostolic tradition, “For the apostles, in the memoirs composed by them, which are called Gospels, have thus delivered unto us what was enjoined upon them.”[8]

Likewise, Irenaeus views all the New Testament Scriptures as the embodiment of apostolic teaching: “We have learned from none others the plan of our salvation, than from those through whom the Gospel has come down to us, which they did at one time proclaim in public, and, at a later period, by the will of God, handed down to us in the Scriptures, to be the ground and pillar of our faith.”[9] Although this is only a sampling of patristic writers (and more could be added), the point is clear. The authoritative role of the apostles was woven into the fabric of Christianity from its very earliest stages.

Second, there is no indication that the early church fathers, as a whole, believed that writings produced in their own time were of the same authority as the apostolic writings and thus could genuinely be contenders for a spot in the NT canon. On the contrary, books were regarded as authoritative precisely because they were deemed to have originated fom the apostolic time period.

A couple of examples should help. The canonical status of the Shepherd of Hermas was rejected by the Muratorian fragment (c.180) on the grounds that was produced “very recently, in our own times.”[10] This is a clear indication that early Christians did not see recently produced works as viable canonical books.

Dionysius of Corinth (c.170) goes to great lengths to distinguish his own letters from the “Scriptures of the Lord” lest anyone get the impression he is composing new canonical books (Hist. eccl. 4.23.12). But why would this concern him if Christians in his own day (presumably including himself) were equally inspired as the apostles and could produce new Scriptures?

The anonymous critic of Montanism (c.196), recorded by Eusebius, shares this same sentiment when he expresses his hesitancy to produce new written documents out of fear that “I might seem to some to be adding to the writings or injunctions of the word of the new covenant” (Hist. eccl. 5.16.3). It is hard to avoid the sense that he thinks newly published books are not equally authoritative as those written by apostles.

Third, and finally, Sundberg does not seem to recognize that inspiration-like language can be used to describe ecclesiastical authority—which is real and should be followed—even though that authority is subordinate to the apostles. For instance, the writer of 1 Clement refers to his own letters to the churches as being written “through the Holy Spirit.”[11] While such language certainly could be referring to inspiration like the apostles, such language could also be referring to ecclesiastical authority which Christians believe is also guided by the Holy Spirit (though in a different manner).

How do we know which is meant by Clement? When we look to the overall context of his writings (some of which we quoted above), it is unmistakenly clear that he puts the apostles in distinct (and higher) category than his own. We must use this larger context to interpret his words about his own authority. Either Clement is contradicting himself, or he sees his own office as somehow distinct from the apostles.

In sum, we have very little patristic evidence that the early church fathers saw their own “inspiration” or authority as on par with that of the apostles. When they wanted definitive teaching about Jesus their approach was always retrospective—they looked back to that teaching which was delivered by the apostles.

[1] A.C. Sundberg, “The Biblical Canon and the Christian Doctrine of Inspiration,” Int 29 (1975): 352–371.

[2] 1 Clem. 47.1-3.

[3] 1 Clem. 42.1-2.

[4] 1 Clem 5.2.

[5] Magn. 7.

[6] Rom. 4.4.

[7] 1 Apol. 39.

[8] Apol. 66.3.

[9] Haer. 3.1.1.

[10] Muratorian Fragment, 74.

Originally published May 21, 2015.