Editor's Note: This article is the second of a two-part piece. You may read Part One of this article here.

It is too ambiguous to speak about the church in the United States as one large, encumbered entity. It is not. It encompasses various denominations and congregations, each with its own subcultures, groups and theologies. Examples of vivid wakefulness can be found—Christians and congregations whose lives are daily demonstrations of God’s heart for justice. However, it still seems broadly the case that either the church is asleep or it may as well be. When measured against the global realities of life on planet Earth that silently scream for attention, the vast institutional life of American Protestantism seems functionally distant and disengaged. According to Scripture, that’s an issue of worship. According to much church culture, there’s no connection between worship and justice.

Many denominations are declining in membership, mine — the Presbyterian Church (USA) — most of all. Each denomination has its own battles over various issues of the culture wars, seeking to be faithful to its traditions and convictions while at the same time trying to respond to today’s circumstances. These discussions are largely internal, often passionate, frequently wounding and alienating to those inside the church but distant and disconnected to those outside it. Meanwhile, on a local level congregations require tending. Individuals and families have needs and crises. When our own immediate world overwhelms us, we can readily feel disinclined or unable to look beyond it.

When we do look beyond, however, we see vividly that the daily lives of millions of people around the world are about chronic desperation. The world is racked with dramatic, torturous suffering as a consequence of poverty and injustice — from human trafficking to HIV/AIDS, from malnutrition to genocide. One-sixth of the world’s population lives in absolute poverty,1 and nearly a million children each year are sold or forced into the sex-trafficking trade. But this is not just about statistics — it’s about real lives. People with names and families are living daily without food or water, in sickness or oppression. Their experience is in their bodies and hearts and minds, not in a global facts chart. They are made with the same dignity and worth as you and me. They have the same capacities and desires. But they are circumstantially without hope. Every day.

All this is going on while mainline and evangelical churches keep debating what they think are the primary worship issues: guitars versus organs, formal versus informal, traditional versus contemporary, contemporary versus emergent; while other denominations are absorbed in debates over issues like gay and lesbian ordination that dominate their landscapes and preoccupy their fading national bureaucracies; and while congregations and individuals alike struggle with their own needs, genuine and personal as they are.

At a time when many are struck by the polarization between liberal and evangelical churches in America, it is more striking to see what the average congregations on both sides hold in common: they are asleep. Some seem asleep to God. Some seem asleep to the world. Some sleep on their right side, others on their left, but either way they are asleep. The way they sleep, the character of their dreams, the forms of their sleepwalking or sleep-talking varies. Varied, too, are the words and voices that cause restlessness, making their sleep less than tranquil: Inclusivity. Diversity. Faithfulness. Process. Power. Justice. Relevance. Recovery. Healing. Biblical. The words may stir the sleeping, but without enough urgency to demand awakening.

Too much sleep can lead to enervation and, in time, atrophy. A crisis hits — 9/11 or the Asian tsunami or Hurricane Katrina, say — and like waking from a deep sleep or shaken by a nightmare, our churches raise their heads and try to rise to the occasion (if they can figure out what it is!). Before long, the clamor of crisis quiets down, and our desire to return to the safe coziness of familiarity is too hard to resist. Wakefulness demands too much energy or strength that cannot be mustered or sustained.

Some Christians and some congregations seem to have selective wakefulness. After all, we are weary, overwhelmed, insecure, internally longing for hope of our own (never mind the need for hope in the world). We don’t see much beyond the edges of our own bed, whether it is culture, economics, race, denomination or class. We know and like our bed. We have made it. We are not inclined to leave it. We are entitled to it after all, since we see it as God’s blessing.

Meanwhile, those without a bed — and without a home, food, safety, water, warmth or knowledge of the Savior’s love — are not seen or remembered or reached. In light of the stark reality of lost and dying humanity, forced prostitution, bonded slavery, malarial epidemics, HIV/AIDS and human life stripped of its dignity around the globe, where is the evidence that through worship our lives have actually been redefined and realigned with God’s heart for justice in the world?

Many of us want to remain asleep. Pastors have in part fostered this somnambulating life with preaching that avoids problems and prophets, controversy and complexity. When preaching plays to the culture without substantially critiquing and engaging it, it becomes part of the problem. Sermons that only apply to the individual and to the inner life of the disciple without raising biblical questions about our public lives are also a factor. So, too, are worship services that offer little more than comfort food: the baked potatoes of love, the melting butter of grace, with just enough bacon and chives of outreach to ease the conscience. All this becomes a churchly anesthetic.

I grew up at the edge of church life, believing that pastors were people who attended to a world of very small things with obsessive care. Now that I am a pastor and work among many other pastors, I confess that this is often true, although perhaps by habit rather than desire. The projects and preoccupations of each day can keep me more than busy. Like most pastors, I want to be a faithful shepherd. I want to focus on the call right before me. That can easily seem like too much on most days, but it can also be small and myopic. It lends itself to sleepwalking, which is already too attractive to many of those we lead.

Jesus, if anything, was and is awake. That’s the shock for those who encounter him in the Gospels. He came to make a world of those who are awake — awake to God, to each other and to the world. Waking up is the dangerous act of worship. It’s dangerous because worship is meant to produce lives fully attentive to reality as God sees it, and that’s more than most of us want to deal with. Yes, true worship always questions the dominant paradigms, even those within the church. It asks whether we are bowing before reality or falsehood, before God or idols.

One of the most dramatic periods of Israel’s history came about because of the nation’s failure to live its worship. God’s criticism of Israel was that it professed what it failed to live. It went through the external signs of worship but failed to live out what the worship was meant to show. The Old Testament prophet Micah distilled Israel’s call at that critical time:

What does the LORD require of you

but to do justice, and to love kindness,

and to walk humbly with your God? (Micah 6:8)

Though frequently quoted, these words are meant to be lived. To do so means we must wake up.

God longs for the church to be awake. God’s grace understands our slumber, while shaking us into wakeful action. The extreme cost of our delirium denies God what is deserved, distorts our humanity and undermines God’s mission in the world. In this book we will consider why and how the disconnection between worship and justice exists as it does, how a more vigorous and encompassing theology of worship can help wake us up, and how faithful worship means finding our life in God and practicing that life in the world, especially for the sake of the poor, the oppressed and the forgotten.

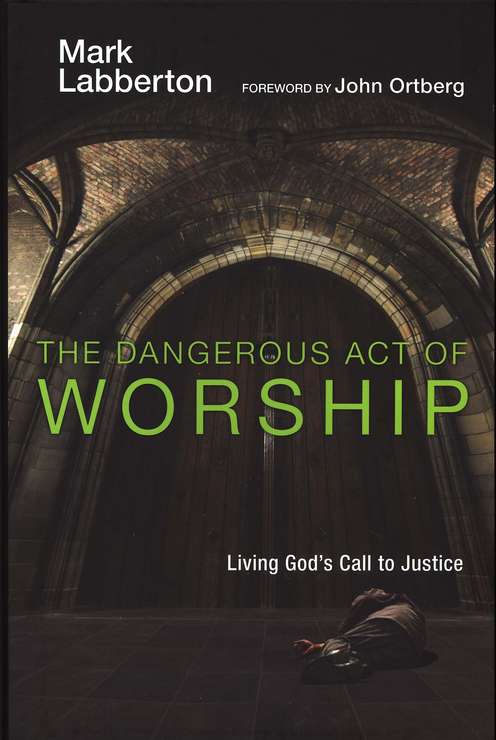

This article is excerpted from Mark Labberton's new book, The Dangerous Act of Worship: Living God's Call to Justice (InterVarsity Press, 2007). Used with permission from the publisher. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

This article is excerpted from Mark Labberton's new book, The Dangerous Act of Worship: Living God's Call to Justice (InterVarsity Press, 2007). Used with permission from the publisher. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

Mark Labberton is senior pastor at First Presbyterian Church of Berkeley in Berkeley, California. He is also visiting professor of biblical studies at New College Berkeley. Labberton received his doctorate in theology from the University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England. He has published articles in Leadership Journal and Radix magazines.