EDITOR’S NOTE: The following is an extract from Suffering and the Goodness of God, edited by Christopher W. Morgan and Robert A. Peterson. This chapter is authored by Robert W. Yarbrough (Crossway).

Chapter One: Christ and the Crocodiles: Suffering and the Goodness of God in Contemporary Perspective

Even newspaper brevity could not hide the harrowing nature of what happened in Costa Rica in early May 2007.1 A thirteen-year-old boy was wading in a placid lagoon. Suddenly he screamed. A crocodile’s jaws had closed on his leg. Like a rag doll he was whisked beneath the water. He surfaced just once. Witnesses say he called to his older brother, “Adios, Pablito.” He blurted out to horrified onlookers never to swim there again. Then there were only ripples.

One report observed that crocodiles do not normally chase and assault their prey. They just lie motionless until something blunders within their kill zone. Another report stated that crocodile attacks are fairly common in Central America and Mexico. An Internet search will readily turn up reports of fatal incidents in Africa, Australia, and elsewhere.

Hardly less unnerving, particularly if you happen to be a parent, is a June 2007 report from North America.2 A family of four was asleep in their tent in a Utah campground: dad, mom, and two brothers, ages eleven and six. In the dark of night the eleven-year-old was heard to scream, “Something’s dragging me!” The frantic parents suspected a violent abduction. Only hours later did they realize that a black bear had slit an opening in the tent with a claw or tooth, sunk its fangs into the nearest occupant, and fled with its flailing booty still in the sleeping bag. The boy’s lifeless body was eventually found a quarter-mile away.

The victim’s grandfather, according to news reports, agonized: “We’re trying to make sense of this. . . . It’s something that just doesn’t make sense. . . . Some things you’re prepared for, but we weren’t prepared for news that our grandson and child was killed by a bear. That’s one of the hardest things we’re struggling with—the nonsensical nature of this tragedy.”3

In this age of Internet connectivity we are aware of life’s incomprehensible cruelties like never before. Sometimes we hear such shocking news within minutes of its occurrence. We even glimpse it live if a videocam or camera phone is at the scene. Most of us have images of the December 2004 tsunami, caught on film under blue skies amid white beaches and palm trees during Christmas holidays, seared in our memories. About 230,000 souls departed this earth within scant hours. TerribleTh Yet more people died of AIDS in a single nation (South Africa) in the next year (2005) than in the tsunami.4 The world is full of the wails of the suffering and perishing to an extent humans can hardly quantify, let alone comprehend. Like the stunned grandfather above, at times all we can do is stop, ponder the ailing and dead, and wrestle with the question, why?

This points to the contemporary significance of the issue of suffering: we cannot escape the fact that it nips at humanity’s flanks in all locales and at all hours. Too frequently the nip is a vicious bite that finds the jugular. And natural disaster, whether a tsunami or a wild animal, is just a small part of the picture. All too much suffering has a direct connection to human intention or negligence: beatings and murders, skirmishes and wars, robberies and riots, tortures and rapes, displacements and bombings, plagues and famines and genocides resulting from human malice. Or take just a single disease: on the day you read this, about 2,500 people will die of malaria, “most of them under age five, the vast majority living in Africa. That’s more than twice the annual toll of a generation ago.”5 Each year one million people die of malaria, and the number is rising. As world population increases, so does suffering.

At the same time, the Christian church around the world and through the ages has the charge of believing and proclaiming the excellencies of a good and loving God, who they claim created this world and whom they profess to love and joyfully commend to others. The juxtaposition of these conflicting claims—the empirical claim of daily calamity on a global scale, and the confessional claim of God’s present and eternal benevolence—touches off the turbulence that this volume explores. By way of introduction, this chapter will unfold eleven theses on suffering’s significance in a world created and ultimately redeemed by the God of historic Christian confession. The cumulative argument will be that suffering must be in the foreground, not the background, of robust Christian awareness today. Yet far from jeopardizing the credibility of claims of God’s goodness, it serves to highlight those claims and draw us toward the God who makes them.

Thesis 1: Suffering Is Neither Good nor Completely Explicable

Current world threats and conditions have given rise to acute consciousness of the human plight. It is therefore understandable that books addressing suffering abound. A quick Amazon.com check will list dozens, with new ones appearing steadily. More than a few of these give the impression that, seen from the right perspective, suffering is actually not all that bad and in fact may just be an illusion. Alongside this move may come the claim to explain (away) suffering to a significant degree—to give a coherent account of its origin, causes, or purposes such that its scandal is essentially dispersed by proper exercise of reason, faith, or some combination of these. I recall a pastor being asked in a Bible study class why God allows sickness and death to come to the people we love and need. His quick and unflinching reply: to bring glory to himself. Maybe there was a history to this exchange between pastor and church member that I was missing, but the tone and implied substance of the reply struck me as pastorally unwise and theologically underdeveloped. (For more on suffering and God’s glory see Thesis 6, below.)

Something is afoot in the world that is on a collision course with God’s wrath, which may be as inscrutable, finally, as the suffering God permits. The Bible uses many words to point to this something: sin, evil, wrongdoing, lawlessness, transgression, suffering, death. Scripture also refers to a superhuman being intimately connected with all that exalts itself against God and delights in defying his truth and trashing his creation: the Devil, the Evil One, Satan, the ruler of this age, the Father of Lies, and the father of murder. The existence of sin and the Devil, and God’s ongoing determination to root them out and finally destroy them, are reminders that a primary existential calling card of this world’s fallenness—human suffering—is not in itself good. Of course God can use it for good purposes and unerringly does so.6 But suffering in itself is not a good thing—as we realize when suffering invades, infects, and affects our lives personally.

If suffering is not something blithely to be called “good,” neither should we allege that it is fully understandable.7 The enormity of human agony associated with either individual or collective experiences of suffering rightly leaves the godliest of persons scratching their heads, if not howling in misery and perhaps repenting in sackcloth and ashes (see the book of Job). Such agony has driven many to suicide in despair. Why did God permit or cause the tsunami, or in another era the Holocaust? Why the woe of Hurricane Katrina? Why the maimed veterans of the Iraq and Afghan wars and of dozens of previous military actions? Why the human carnage on the ground in the lands in which those wars were and are being fought? Why Joni Eareckson Tada’s paralysis,8 or fifteen million AIDS orphans in Africa? Even Jesus asked a question about the mystery of sin and suffering: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matt. 27:46).9 How much more should we decline to claim for ourselves a reasoned, settled mastery of suffering, its causes and purposes, and its effects?

Thesis 2: Suffering in Itself Is No Validation of Religious Truth

The Baal prophets oozed blood from self-inflicted wounds (1 Kings 18). Jesus spoke of agonized self-denial that advertised itself (Matt. 6:16) and Paul of self-immolation by burning (1 Cor. 13:3). The quasi-religious Stoics of antiquity upheld suicide as a noble trump card for making a rational statement in the face of cosmic adversity. Many religious assertions are backed by reports of individual or collective suffering for the sake of the cause. Mormons recall the opposition they and their early leaders faced, for example, in Illinois and Missouri. Certain Muslim groups can point to present or historic sufferings to bolster their claims about proper politico-religious order in Islam. Real or perceived unjust suffering at Israeli or US-British hands may be used to justify suicide bombings at least partially in the name of religious interests.

This volume will study and at times commend suffering as a possible condition or entailment of a living faith in Jesus Christ. But it should be understood that suffering in itself, although commanded and modeled by Jesus, is by no means always a token of faithful Christian discipleship. There are many reasons for this. Our suffering may be brought on by our own folly rather than noble decisions or actions. Ministers who molest children cannot plead the sanctity of their vocation to avoid a prison sentence. Or our suffering may be the result of false religious claims, not true ones. A theology professor who loses his job for teaching that is way off base may be getting his just deserts. Or our suffering may be the result of immaturity or bad judgment or self-righteousness. A youthful church staff member who is dismissed for upbraiding the congregation during Sunday morning worship could be serving as a courageous prophet—but she could also be giving in to petty anger, a rebellious spirit, and an unwillingness to trust the Lord of the church regarding matters for which she has no business condemning others.

The point here is that keen discernment is required for accurate assessment of suffering. It is not as easy as saying, “I suffer for these convictions; therefore, these convictions are sound.” That could be the case. But those words could also be delusional. In an era like ours, where both suffering and demands to be heard based upon it are ubiquitous, careful reflection guided by Scripture’s teaching, God’s personal guidance, and the collective wisdom of God’s people are essential. Hence this book.

Thesis 3: Accounting for Suffering Is Forced upon Us by Our Times

This book originates in the United States, a land of relative security and affluence. There have been decades within living memory where North Americans, most of us healthy, well-fed, and gainfully employed, could live relatively untouched by acute personal consciousness of many kinds and dimensions of suffering. Starvation, imprisonment for Christian faith, and being “tortured for Christ” (the title of Richard Wurmbrand’s famous book) have sounded distant, exotic, and vaguely unnecessary. Naïveté and obliviousness to suffering, especially by Christians for their faith in Jesus, probably should never have been so prevalent in the North American church, composed of ostensible followers of Jesus, who took up a cross and taught his disciples to do likewise. But suffering has been widely overlooked or suppressed, as in too many quarters it continues to be.

The days are now over for this mentality to be countenanced. A summer 2007 edition of a national newsweekly, for example, carried a four-page ad for The Voice of the Martyrs smack in the middle.10 There were two tear-out cards. Anyone with a mailing address can request a free monthly newsletter. Much the same information and offer appeared in the July 2007 Reader’s Digest. Anyone with Internet access can visit www.persecution.com and find out more than enough to break even a stony heart. (Just google “Christian persecution” for numerous other sites.) Anyone with a conscience and a sense of urgency to honor Christ can find multiple ways to become aware of, and respond to, the dire, ongoing, and increasing human misery and need.

The point is that what the din and self-preoccupation of the American way of life (often equating to pursuit of material security and self-indulgence, measured by gospel standards) may formerly have obscured—the terrible suffering of persecution—has now gone mainstream. There is no excuse for pastors or churchgoers failing to wrestle with our and my obligation to put a shoulder to the wheel of the task of selfless and long-term Christian response—and perhaps even personal exposure—to suffering for Christ’s sake.

Nor can we reduce the task here to responsiveness to only Christian suffering. Jesus wept over Jerusalem, not just for followers who he knew would suffer for his name. The problem of suffering includes but extends beyond the circles where fellow Christians are especially affected. It may be that our collective will to embrace this issue with moral seriousness will prove to be either our salvation or our undoing. It may be, for example, that the responsiveness of upcoming generations—believers between, say, childhood and young adulthood—to the gospel message propounded by their parents and leaders hinges largely on the urgency with which we respond to the suffering that cries out to us from every direction and emerges from the shadows of our own lives. Will we encourage the young to a response that will move beyond the probably pitiable foundation we may manage to lay? Or will we, like contemporaries of Jesus, be guilty of raising a generation who are twice as much children of hell as we are (Matt. 23:15)? To flinch or take umbrage at this question probably indicates lack of knowledge of the enormity of the task at hand. It could also indicate self-righteousness in the face of crisis that should long since have driven us to profound repentance and transformed life direction.

Thesis 4: Suffering May Be a Stumbling Block to Gospel Reception

One impediment to suffering getting due attention in some quarters is lack of awareness of its corrosive effect, in principle, on people’s receptivity to the saving gospel message. In early Christian centuries the suffering caused by earthquakes, plagues, and other calamities was actually blamed on Christians, who were sometimes hounded and punished for their presumed destructive mischief. Suffering served to impede reception of the Christian message.11 In more recent times, the Lisbon earthquake (1755) shook the faith of Europe as it claimed the lives of perhaps one-third of Lisbon’s 275,000 inhabitants. It took place on November 1, All Saints’ Day, a religious holiday when many would have attended mass. Philosophers of immense influence like Voltaire, Rousseau, and Kant concluded that the notion of a benevolent God directly superintending all human affairs was no longer tenable. This conviction persists today among many, from the unlettered to the intellectual elite.

The catastrophic loss of life in the trenches of World War I and the historically unprecedented brutality of new war technology (machine guns, high explosives, chlorine gas) are widely credited with shattering the cultural optimism of Europe and prompting a turn away from Christian or even theistic belief in Western intellectual culture, including the United States. World War II brought its own set of moral monstrosities, as wars always do—but with the unique features of the Holocaust and then the atomic bomb detonations in Japan. Looking back on the twentieth century as a whole, it is indeed justified to speak of “a century of horrors.”12

North America has been untouched by the devastation of its cities, countryside, and population that many other nations of the world have experienced in recent generations. This may account, in part, for why a much larger percent of the population here still attends church than in other nations. We may well be thankful that we have been spared so much grief. At the same time, we should not let our good fortune make us callous to the effect of suffering on most of the world’s population. We are a land still rich in the presence of churches and denominations that are committed, in principle, to sending the light of the Christian message to all peoples, locally and beyond. But we will be hamstrung in our mission to the extent that an overly rosy view of life and God, derived from our relative freedom from destitution and suffering on the scale common elsewhere, infects and distorts our theological reasoning and outreach. Historically this has sometimes taken the form of a hypocrisy eager to preach the salvation of souls but too stingy to address listeners’ material needs as well.

To summarize, the problem of suffering may seem distant to us, whose “suffering” may arise chiefly every decade or two when we or a loved one receives an unfavorable medical report. We need to open our eyes to a larger historical and geographical context. We cannot pray for, speak to, and serve with integrity alongside Christians of our era worldwide if we underestimate the relevance of suffering to all we seek to do in Jesus’ name. We will either lack motivation for radical discipleship, not being gripped by and possibly sharing in the pain of others elsewhere, or we will tend to propagate and export a distorted rendering of the gospel, one that comports with our prosperous setting but does not ring true among the majority of the world’s peoples, who on a daily basis live close to bare survival’s jagged edge.

Thesis 5: Suffering Creates Teachable Moments for Gospel Reception

Jesus did not evade the issue of suffering and neither should we. One day as he was teaching (Luke 13:1–5), he was informed of Pilate’s murder of some Galileans who were in the very act of worshiping God. We do not know all Jesus said. But we know he leveraged the shock of the hour into an object lesson, urging listeners to make a life change. He even took it a step further by pointing to a building collapse that claimed the lives of eighteen people. The lesson he drew from this tragedy was the same: Repent, lest you too perish!

There is much more to say about suffering than “Consider your ways and turn to God!” But Jesus reminds us of that standing imperative. If we dare deepen our comprehension of suffering vis-à-vis God’s goodness— cognizant that “he who increases knowledge increases sorrow” (Eccles. 1:18)—we do well to seek ways to emulate Jesus’ acknowledgment of suffering as an occasion for human affirmation of God.

We have already argued that this does not make suffering in itself a good thing (Thesis 1 above). But it does encourage us to enlarge our outlook to incorporate suffering into our view of what it means to come to Christ and then to honor and serve him. We do not trust in him so that we can evade suffering, nor do we present Christ as an assured means of escape from hard times. Rather we trust so that in good times and bad our lives will reflect fidelity to him and the courage that Jesus modeled and imparts. The same suffering that hardens some or drives them to faithless despair can be an occasion for the bold move of hope in Christ in spite of suffering’s disincentives to affirm and believe in God.

We do well to remain intent on enlarging our spiritual understanding so that we become tougher and wiser when it comes to absorbing and responding to suffering. As we do so we will become more effective messengers of the gospel to others whose sufferings may likewise be the occasion of making the right choice when faced with the question: should I let adversity drive me away from the Bible’s testimony to God’s good purposes and eternal promise, or should I believe that the message of Jesus and the cross are still adequate grounds for personal faith in him? It is often suffering that makes this anguished but fruitful outcry unavoidable and that also paves the way for the best, though usually not the easiest, response.

Thesis 6: Suffering Will Bring Glory to God in the Lives of Believers Subjected to It

Joseph affirmed this when he uttered the famous words to his conscience-stricken brothers, “As for you, you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good, to bring it about that many people should be kept alive, as they are today” (Gen. 50:20). Jesus stated that behind a case of congenital blindness stood divine intention: the blindness came about not because of the victim’s or his parents’ sin, as many supposed, “but that the works of God might be displayed in him” (John 9:3). Jesus’ opponents demanded of the man, “Give glory to God” (John 9:24). Through many years of suffering blindness, this man was in a position to do precisely that when Jesus touched his life, and he responded with brave and costly devotion.

People of authentic Christian faith are still glorifying God through sometimes unspeakable travail. A recent issue of Trinity Magazine (Spring 2007) soberly recounts a pair of such situations. Since I teach in the institution that produces this publication, Trinity International University, these tragedies strike me with personal force. In the first case, Gwen Voss, a twenty-seven year-old librarian of great beauty, intelligence, and importance to Trinity’s Rolfing Memorial Library and the international ministry it supports, was admitted to the hospital for a fairly common procedure, the reopening of a collapsed lung. Her long-awaited wedding date lay just one week ahead. She was, doctors thought, one day from discharge. But during an amiable conversation with her mother at her bedside, an undetected embolism moved from her leg to her heart. Unconsciousness and death were immediate despite forty-five minutes of resuscitation efforts, including fervent prayers by her parents and fiancé. Finally, her father, Tim, chair of the Human Performance and Wellness Department in Trinity College, told the doctor, “Let her go.”

The brief account of this September 2005 event and its aftermath does not even bear a writer’s name.13 Two things stand out. One is the depth of the parents’ grief. From her mother, Kathy: “That first year, there are times when you feel you can hardly breathe.” From her father, Tim: “Now, a year later, I find myself really beginning the grieving process as a dad of not having Gwen in my life.”

The second striking feature is the depth of conviction that, despite the sudden death blow, God was not unfaithful. From Kathy: “As a mom, I wanted to say, ‘God, you had no right to give her and take her away from me.’ But reading Philippians [2], I realized that Christ did not cling to his own rights, and God did not cling to his own Son.” From Tim, who has often sought solitude outdoors: “God really does come beside you—a strength, a peace, a covering.” He continues: “At your core, you know that you are not alone . . . even when the people in your life, your job, are not enough. You really need God. He is acquainted with grief, with the depth of grief. He finds ways to make himself evident.”

Christian believers, particularly any who have faced a similar staggering loss and yet have tasted divine comfort, may well agree that the testimony of Tim and Kathy Voss, both to their agony and God’s sufficiency, gives due deference and honor to God.

No less poignant is the case recounted by my colleague John S. Feinberg.14 Before he and his wife, Pat, married in 1972, they took special care to assure that the long-term illness of Pat’s mother could not be passed along to their children, should they have any. Doctors confirmed that neither Pat nor any offspring were in danger; the malady had no hereditary dimensions or implications. Yet some fifteen years later, in 1987, Pat was diagnosed with her mother’s disease. As I write twenty years later, her condition slowly worsens. The prognosis is death. Any or all three of their children may succumb to the same affliction. John writes:

“Although I had spent much time in my life up to this point thinking about the theological problem of evil (I wrote my doctoral dissertation on it [at the University of Chicago]), I couldn’t make sense of what was happening. How could this happen to us when we had given our lives in service to the Lord? I knew that believers aren’t guaranteed exemption from problems, but I never expected something like this. I was angry that God had allowed this to happen.”

John Feinberg writes of finding particular challenge and insight in verses from Ecclesiastes 7 and Matthew 20. Although he states that “in November 1987, Pat’s diagnosis gave me a view of the future that just about destroyed me,” he goes on to speak repeatedly of his wonderful wife and children, his love for them that the hardships have only enhanced, and of his gratitude:

“While there are still many things about our circumstances that I don’t know or fully understand, I do know some things with certainty. I know that throughout eternity I’ll be thanking God for the wife and family he gave me and for the ministry he has allowed us to have in spite of (and even because of) the many hardships. I am so thankful that God is patient with us and always there with his comfort and care.”

As in the case of Tim and Kathy Voss, John and Pat Feinberg had a head-on collision with suffering. Their convictions and, in their view, the reality of a benevolent God who is personally present, have resulted in a testimony that surely glorifies God. It would be facile and flippant to say “terrible thing x” happened so that “wonderful thing y” would result, x being death and disease and y being God’s glorification. The Vosses and the Feinbergs do not trumpet final answers that dissolve the pain and questions that they will, no doubt, carry to their graves. Yet it is clear that adversity, and their suffering, have not had the last word. Among believers, suffering is an important factor in God’s answering the prayer Jesus taught us: “Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name.” His name is hallowed through his children’s suffering.

Thesis 7: Suffering Is the Price of Much Fruitful Ministry

Christians are called to be servants—of God, of one another, of their spouses and other family members, of friends, of the world at large. Jesus “went about doing good” (Acts 10:38) and came not to be served but to serve and give his life (Mark 10:45). His selfless pattern was an intentional example for his followers: “For I have given you an example, that you also should do just as I have done to you” (John 13:15).

Jesus’ call to serve is also, probably too frequently for our liking, a call to suffer. “Suffering seems to be one of those things God has for us that has to be dealt with personally in order to come to grips with it in others, Christian or not.”15 John Feinberg has written several powerful books on God, on evil, and on suffering.16 But this enviable ministry in print has come at the price of circumstances none of us would wish on anyone or volunteer for ourselves. Many great sermons on suffering have grown out of lives torn apart by pain, whether the preacher’s own or those to whom he ministered. Some years ago Warren Wiersbe produced a useful sampling of such sermons by Arthur John Gossip (1873–1954), whose wife had just died; by John Calvin (1509–1564), whose health and surroundings constituted a severe trial for much of his adult life; by Frederick W. Robertson (1816–1853), who wrestled with depression and died young; and many others.17

Today books abound on the integral link between Christian service and testimony on the one hand, and suffering on the other. Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s (1906–1945) rich legacy, still very much alive through his printed works, harks back to years under Nazi oppression and eventually imprisonment and execution. Peter Hammond has written extensively about his harrowing experiences in Sudan.18 Isaiah Majok Dau, a Sudan native, grew up amidst the terrors of Islamist oppression of the southern part of his native country. While the persecution of millions was not always overtly religious, at least tens of thousands died as the result of their confession of faith in Christ. Dau has produced one of the most important modern studies of suffering in Christian perspective, written from within the epochal war in Sudan and interacting with ruminations at least related to the subject of suffering by many Western theologians for whom the whole issue is largely theoretical.19 The aftermath of the history Dau analyzes continues today in events unfolding in Darfur with its government-sanctioned janjaweed, terrified local populaces, and windswept mass graves.

Dan Baumann was falsely accused of espionage in Iran and endured prison and the threat of execution as a result of his Christian vocation and activities.20 Bonnie and Gary Witherall followed the Lord’s call to service to Lebanon, where Bonnie was killed in cold blood in the midst of selfless service through medical care and Christian outreach in the city of Sidon.21 New details continue to emerge regarding Stalin’s Russia, where Orthodox Christians were put to death to the tune of six hundred bishops, forty thousand priests, and one hundred twenty thousand monks and nuns. Many more rank-and-file believers were killed, of course. “They suffered and died for their faith, for the fact that they did not renounce their God. In dying they sang His praises, and He did not abandon them.”22

This is but a smattering of reference to a large and increasing literature that we ignore to our peril. The blood of our (often fatally) faithful sisters and brothers cries out to us from the ground. Their service was fruitful, and their enduring testimony is immensely rich. But there was a daunting entailment: Jesus’ call to take up a cross became something more than a metaphor.

Thesis 8: Suffering Is Often the Penalty for Gospel Reception

A tension has arisen in some quarters in recent decades between viewing the gospel as a means of blessing, of gain, of prosperity on the one hand and viewing it as a call to personal loss and self-abnegation on the other. “Health-and-wealth” renderings of the Christian faith have arisen that focus largely on the benefit promised those who respond to the gospel message in the right way.23 This has not been limited to North America, from which it has been aggressively exported. My own travels in Eastern Europe and Africa confirm how widely this notion of Christian teaching and life has spread in many corners of the globe. It can also be documented in rapidly growing segments of Christian populations in Asia and South America. Prosperity teaching is spread widely through satellite television and vies with older, historic, more balanced, and more austere understandings of what it means to believe in and follow Christ.

It is not to be doubted that God can and frequently does shower boon of all sorts, material included, on his beloved children. Yet offsetting the siren song of wealth and plenty are sobering reminders that God may choose to make the reception of his saving word a decidedly mixed blessing.

Consider this actual email plea to “Brother Mohammed,” a convert from Islam to Christianity who ministers on a North American university campus, from “Salwa.” (All names have been changed for security purposes.) Salwa and her husband, both devout Muslims, are studying in the States, and Salwa saw the Jesus film. According to their faith and custom, Salwa should not be communicating with a man who is not her husband, and she should certainly not be entertaining thoughts of believing in Christ à la Christian teaching. Now she finds herself in a gripping quandary. She writes clandestinely for counsel:

“Brother Mohammed,

"How are you today. Hope every thing is OK.

“First, I hesitated so much before sending this e-mail. I did not want to do something behind my husband’s back, but I’m just looking for the truth and trying to find some answers to many, many questions I have. And I know for sure that we use this method (e-mail) for only that reason.

“You might know the reason for this e-mail. I think you’ve heard the condition that I’m in since I saw the movie. I was wondering if someone from the same background that I came from can help me finding my way. Now, I’m really confused! Mohammed, how did you find your way? How did you start? and when? How did you become a believer? and how do you behave after that? What is the difference between now and then?

“What about what we all learned under the umbrella of Islam? I have endless questions. Mohammed, please, help me find my way! I can not help thinking of Jesus since I saw the movie but, what I’ve been taught for the 30 years prevents me from submitting. Were we wrong? were we right? where is the truth? Life is not long enough, so we need to search for the truth as soon as we can.

“My husband does not know about this e-mail, so, please, you respond to this e-mail only, not to the other ones. He has an access to my campus e-mail. Thanks, I appreciate your interest in helping me.

“Salwa “

Who can fail to be moved by this situation? If Salwa continues to follow through on this, the personal and social cost to her will likely be staggering. This is assuming that she does not become one of several thousand “honor killings” that take place each year in certain quarters of the Arab world.

Following Christ may in fact have a result quite different from the blandishments of prosperity-teaching proponents. It is not only the woman “Salwa” who grapples with this; it is also “Mohammed,” her contact—he has family members in the Middle East ready to do him harm for leaving Islam. He lives in delicate contact with them, praying for them and socializing when it seems safe, but trying to avoid situations in which they could find it easy to strike him down for embracing Christian convictions.

There are tens of millions of Christians resident in the Middle East24 whose testimony faces just this sort of stony reception. There are hundreds of millions of Muslims whom Christians worldwide are called to love, pray for, and evangelize. It is hard to see how this task can even be taken seriously, let alone aggressively pursued, under the auspices of a message that conditions “Christians” to seek their own material benefit. Certainly such a message has nothing credible to offer “Mohammed,” “Salwa,” or innumerable others in analogous settings. The contemporary setting calls for clear-eyed recognition of the real cost of discipleship for vast reaches of today’s world population.

Perhaps the last words of this section should call attention to the terse lines of a memorial posted in honor of American medical missionary Martha Myers, gunned down with several others in Yemen in December 2002. The penalty for her commitment to her calling was ultimate. The account speaks for itself:25

Slain Missionary, Dr. Martha Myers, “Gave Her All to People Who Were Suffering”

Birmingham, Ala.—Dr. Martha C. Myers, the Southern Baptist missionary shot to death by an extremist in Yemen Dec. 30, was remembered as a person “mature beyond her years, especially in her Christian commitment,” by a former teacher.

Dr. Mike Howell, her biology professor at Samford University, described Myers as a well-rounded person but one who was “absolutely serious” about becoming a medical missionary.

“She was a brilliant, hard-working person, good in things other than biology,” he said. “She sang in the A Cappella Choir and edited the literary magazine, but there was never any doubt among the faculty that she was headed to the medical mission field.”

Dr. Myers graduated from Samford in 1967 and the University of Alabama Medical School in 1971. An obstetrician, she served at Jibla Baptist Hospital in Yemen for more than 25 years.

“There aren’t many people willing to dedicate their life to people, but she gave her all to people who were suffering,” Howell said. “That’s the greatest calling of a Christian.”

Her father, Dr. Ira Myers of Montgomery, Ala., recalled his daughter speaking of the great need for medical care in Yemen. “She just depended on the Lord to take care of her,” he said. “This is what she felt she ought to be doing and she did it.”

Myers was killed along with two other hospital staff members, administrator William Koehn and purchasing manager Kathleen Gariety. Koehn’s daughter, Janelda Pearce of Mansfield, Texas, is also a graduate of Samford’s nursing school.

A classmate of Myers at Samford, Bonnie Barnes Voit of Cullman, Ala., recalled that Myers had a commitment to medical missions that was “as clear as crystal” when they met as freshmen in 1963. “This clear call she felt to serve others empowered her even as a freshman majoring in premed.”

Catherine Allen of Birmingham, another classmate, said Myers was “very focused and very productive.” It was this focused personality and “a distinct calling of God” that enabled Myers to serve for so long in Yemen, said Allen.

“The Yemen hospital was the most enduring, visible and viable International Mission Board witness in the Middle East,” said Allen, a former administrator of the Woman’s Missionary Union.

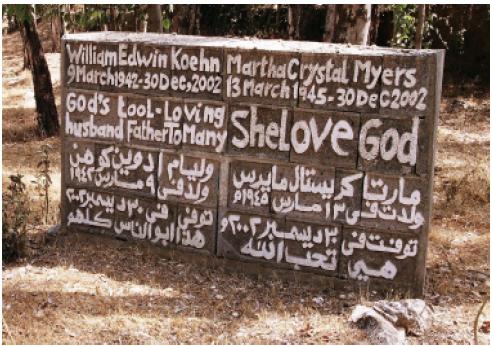

Myers and Koehn were buried on the grounds of the hospital they had served for a quarter of a century.

That is an official summation of a recent martyrdom in Christ’s service. Thanks to a personal friend who visited Yemen shortly after Dr. Myers’s death, I can fill in some background, edited from my friend’s personal journal.26 There were three murders that day: Kathy Gariety, Martha Myers, and Bill Koehn. But the target was Martha. She was an obstetrician/surgeon at the hospital. She died penniless, having sold her furniture and other possessions to give to the poor. She traveled all over the region inoculating children and caring for the sick. She had earlier befriended her killer’s wife and had shared Christ with her. Consequently he determined to kill her and planned the murder for many months. During this time he became associated with Al Qaeda. On the day of the killings he called the hospital and had Martha paged. This way he would know that she would be at the telephone in the hospital office. He smuggled a pistol in with him, went straight to the office and shot and killed her. He then shot Bill Koehn, who was seated at the desk beside Martha, and Kathy Gariety, who also happened to be in the office. He went to the next room and shot the pharmacist, who would later recover.

There is an interesting sequel. The first time Baptist personnel from the hospital went into Jibla after the shooting, people hid in their doorways. Given the law of retribution that is so much a part of their culture, they were afraid that the hospital staff would be out for blood, seeking vengeance. When it became obvious that no attack was forthcoming, the people flocked to the staff members, fell on their necks, and wept with them. Bill’s widow, Martha Koehn, continues to serve at the hospital where her husband and Martha Myers are buried, up on the hill above the staff housing. The burial site is shown in the photograph below (used by permission):

Thesis 9: Suffering Nobly Borne Testifies to God’s Goodness

This book is not only about suffering but also about God’s goodness. It is suffering that poses the major problem. Who is going to resent God’s goodness? Yet we live at a time when divine beneficence, at least in any form associated with religion and particularly with Christianity, is hotly disputed.27 Telling responses to these attacks are appearing,28 and more, perhaps more reflective ones, may be expected. But while many people in the world probably sympathize with these attacks, far fewer will read or even be aware of their rebuttals. How does goodness in the world, when it becomes evident and visible, come to be associated with God?

The Bible suggests that people infer at least certain divine attributes from creation (Rom. 1:20). Jesus pointed to birds, flowers, and grass as signs that God cares for humans, too (Matt. 6:26–30). Scripture is studded with claims that God superintends the world and that his provision is rich and good. An example can be seen in Psalm 104:10–15:

“You make springs gush forth in the valleys;

they flow between the hills;

they give drink to every beast of the field;

the wild donkeys quench their thirst.

Beside them the birds of the heavens dwell;

they sing among the branches.

From your lofty abode you water the mountains;

the earth is satisfied with the fruit of your work.

You cause the grass to grow for the livestock

and plants for man to cultivate,

that he may bring forth food from the earth

and wine to gladden the heart of man,

oil to make his face shine

and bread to strengthen man’s heart.”

Yet even if it is true that many find God to be good as the result of the natural blessings they receive from his hand, others do not. The Bible acknowledges this, too (Rom. 1:21). The goodness of God in the world at large cannot be quantified and “proven” to the earth’s inhabitants. If God is good, and if acknowledgment of him in his goodness is integral to coming to terms with him as the God who saves, impressing this goodness on people becomes vital. How can this be accomplished? The question becomes all the more urgent in the postmodern setting with its suspicion of truth claims and metanarratives.

One response to this problem is to show that, even in the face of contemporary philosophical animus against historic Christian belief,29 credible strategies still abound for effective testimony even in the academy where post-, non-, and anti-Christian views are so entrenched and virulent.30 But most Christians are not called to this venue of discussion and debate. What Christians at large can do is in some ways greater in scope and extent. They can bear their circumstances, including the painful ones, in ways that testify to God’s goodness even if that testimony is rendered through tears. This may be as effective an apologetic for the goodness of the God they serve as anything else they could do or say.

When Jesus wept at Lazarus’s grave, it moved even “the Jews” (in the fourth Gospel often a term describing Jesus’ detractors) to pity: “See how he loved him!” (John 11:36). Jesus’ grief, borne within his whole life’s affirmation of the Father’s goodness, moved his enemies’ hearts to sympathy even though their minds were set on opposing his message. The same dynamic may be observed today. Often funerals of Christians become occasions for moving witness to the gospel message by those still living. I recall reports of a Christian physician killed in a car accident on a snowy road as he traveled for ministry purposes. During the closing hymn of the jam-packed memorial service his five sons stood, joined hands, and raised their arms aloft, proclaiming without words their belief in Christ’s triumph over death despite their father’s most lamented passing.

The argument here is in a sense no newer than Tertullian’s ancient observation that the blood of Christian martyrs is often the seed of the church.31 God uses pain and even death—not in the abstract but of his own loyal people—to testify to the word of life. What is called for today is a growing core of Christians not who have martyr complexes but whose daily lives are lived in such winsome, habitual, and cheerful self-sacrifice that they can weather even adverse circumstances with God-glorifying wisdom and grace. Job managed it in his day. Psalm 90, the only psalm attributed to Moses, shows that his belief in God’s goodness was absolute despite acute earthly duress. Early Christians such as Paul and Peter wrote from within settings where difficulties abounded, but they did not hesitate to exhort others to “share in suffering as a good soldier of Christ Jesus” (as Paul writes to Timothy in 2 Tim. 2:3; cf. 1 Pet. 4:1). That is a major contention of Hebrews 11.

We live in a time when many have laid down their lives in faithfulness to their Lord who, they are convinced, is good and perfect in all his ways. The fact is that Christian suffering nobly borne may serve to impress upon a skeptical or indifferent world that the God of Christians is as good as or better than he is professed to be by those who endure hardship for his sake with aplomb and even praise. This witness, for some, may be more persuasive than formal argument alone could ever be.

Even if none are convinced, the virtue of the confession remains. People who have gone down in flames in one era have been known to kindle fires of fresh belief in subsequent times by their moving affirmation of God’s goodness in the face of high cost to themselves. Cain’s murdered brother, Abel, “through his faith, though he died, . . . still speaks” (Heb. 11:4).

Thesis 10: Suffering Unites Us with Other Sinners We Seek to Serve

Suffering is the quintessential leveler. “Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee” (John Donne). We all face death eventually. In the meantime we are subject to the tremors of a world made uncertain by sickness, setback, sin, and the unwelcome unexpected in general.

A possible response to this is to stress the power of God to deliver us from what we dread. God’s goodness, and his willingness and power to exercise it, are a grand theme of Scripture. Christians proclaim the God “who is able to do far more abundantly than all that we ask or think” (Eph. 3:20). Yet in the long run circumstances overtake the bravest and most sincere affirmations of God’s victory over adversity. That ultimate victory is not in doubt. However, human capacity for leveraging it to our temporal, financial, medical, social, political, or other personal advantage will always prove limited in the current age.

Rather than chasing the wind of perpetual success and triumph, the Christian call is to recognize frankly how profoundly united we are with all other people on the face of the earth. It is our suffering, finally, that confirms and cements this solidarity. We watch our parents age and weaken and pass away, and eventually see the same decline in our own lives. We struggle with our children’s problems and realize repeatedly that in the end they must work out their issues for themselves. Like others, we Christians receive disastrous medical test results. We lose our jobs. Our spouses may betray us. Our retirement funds take a hit when financial markets tank, and our good-faith efforts to further the Lord’s interests may seem fruitless despite our best efforts. Or perhaps poor health and sporadic employment make retirement funds an unattainable dream.

The earth yields not only bounty but also thorns and thistles. Recently, word arrived of the death, after much suffering, of Harold O. J. Brown, founder of Care Net. This organization consists of 1,090 pregnancy centers across North America helping over one hundred thousand pregnant women annually find alternatives to abortion. This man’s efforts, we could say, helped save a million lives or more. Yet he was not untouched by the general entropy of life in this fallen world. No one is.

This fact is one reason why suffering must be in the foreground of Christian thought and action today: it is a ready bridge between those who have the word of life and those who do not. This is apparently part of God’s evangelistic strategy. Even Jesus was “a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief” (Isa. 53:3). Was this part of what drove the centurion to profess Jesus’ innocence, and why “all the crowds that had assembled” to gape at Jesus’ death returned to their homes “beating their breasts” in apparent empathy? Christians’ lives and message gain credibility in part because they are not spared the vicissitudes that batter everyone else in need of God’s redemptive promise.

Thesis 11: Suffering Establishes True Fellowship among Christians

Paul longed to know not only the power of Christ’s resurrection in his life but also the fellowship of his sufferings (Phil. 3:10). Reinhard Hütter in his volume Suffering Divine Things examines, among other matters, “the pathos characterizing the core of Christian experience.”32 Christians have in common not first of all that they “do” something to make themselves Christian but that they are acted on from outside their own puny force of intellect, feeling, or will. There is an “other” which “determines or defines a person prior to all action, in all action, and against all action, an ‘other’ which a person can only receive.”33 This “other” is, first of all, God himself in his saving self-disclosure. But it is also the adversities of life from within which God makes himself known. Luther in particular unfolded “the pathetic heart of Christian existence.” He did this using “the terminology into which this Greek pathos and all its semantic variants have been translated into Latin, namely, as passio.”34

Hütter explores this insight in its significance for a Christian doctrine of the church. It is equally important for hinting at the contemporary significance of suffering (related to the Greek word pathos and the Latin passio). It is certainly true that it is primarily God himself who in his redemptive activity has “caused us to be born again to a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead” (1 Pet. 1:3). But this new birth does not take place in a vacuum. Rather it unfolds amidst earthly life, which is manifestly to some extent a vale of tears. Christians are divided in many ways by doctrinal, social, geographical, economic, racial, and other distinctives if not barriers. They have in common, however, not only their knowledge of God in Christ but also their subjection to forces and circumstances that constitute suffering.35 They also share a common mandate to suffer, as many subsequent chapters in this book will demonstrate. Just as this creates important solidarity with other humans at large (Thesis 10 above), it is an insight—and ultimately an experience—rich with potential for encouraging mutual Christian sympathy, shared undertakings, and the affirmation of one another that is primary amidst a fellowship whose principal affective badge is their love for one another (cf. John 13:34–35).

Conclusion

Naturally the theses above do not begin to exhaust what could be said regarding the contemporary significance of suffering in a world replete also with tokens of God’s goodness. We have said nothing, for example, of the fact that what befalls us in life is a perennial spur to a truer and better faith. We are forced to move beyond the important relational principle that believers have a gift of personal fellowship with God to the doctrinal principle that this personal fellowship is rooted in theological truth and does not replace it.36 “Although charisma probably does indeed constitute the inner dynamic of the church, it is not its foundation.”37 Suffering is a bracing slap in the face that drives God’s people again and again to clarify and purify the fundamental terms of acknowledgment and worship of their God. It drives us to turn our hearts to God in truer prayer. The rediscovery and application of a brutally realist God-centeredness is an urgent need in an era of much crass human-centeredness—typified recently in the ego-centered absurdity of Episcopal priest Ann Holmes Redding’s simultaneous profession of both Christian and Muslim faith.38

Nor have we explored implications of the fact that whatever suffering Christians and everybody else must endure in this world, it pales next to scriptural predictions of what awaits the divinely accursed both in this age39 and in the age to come.40 This has contemporary significance in that contemplation of both current and eschatological woe is an important incentive to cultivate a seemly sense of urgency in personal pursuit of God, in ecclesial labors including evangelism, and in mission generally.

But the last word of this introductory chapter belongs not to one more thesis or argument but to a story. We began speaking of a boy’s death by crocodile in Costa Rica. No one could save him. A second story, very similar, has a different ending. In the Nseleni River near subtropical Empangeni, South Africa, two third-graders released from school with pinkeye decided to slip away for a secret swim. As they were leaving the water, a hidden crocodile’s jaws closed on Msomi’s leg. He shouted frantically for help. Companions wisely and understandably fled.

Except for Themba. He grabbed his friend Msomi in a tug-of-war with the determined reptile. Matters hung in the balance for a long turbulent moment. Suddenly Msomi broke free. He scampered out of the water, bleeding from his left leg and arm and from a cut across his chest. But he was saved.

And Themba the noble rescuer, a third-grade kid with the heart of a grizzled warrior? Msomi, visibly shaken, lamented from his hospital bed: “I ran out of the water, but as Themba tried to get out, the crocodile caught him and he disappeared under the water. That was the last time I saw my friend alive. I’ll never forget what happened that day—he died while trying to save me.”41

The crocodiles of crises and calamities beset us all. Eventually we wander into the kill zone where the unwanted lurks, biding its time. Suffering is ubiquitous and finally terminal in this age. But there is a God, and he is good, and those who seek him are saved. We are all Msomi, but there is a Themba. The chapters that follow explore our dilemma and our deliverance, beginning with two that survey the Old Testament and suffering from the pen of Walter Kaiser.42

Footnotes:

1. Reuters, “Crocodile Makes Off with Boy,” TVNZ, 5 May 2007, http://tvnz.co.nz/view/page/1098603 (July 11, 2007).

2. Catherine Elsworth, “Bear Kills Boy After Pulling Him from Family Tent,” Telegraph.co.uk., June 20, 2007, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/global/main.jhtml?xml=/global/2007/06/20/wbear120.xml (July 11, 2007).

3. Ibid.

4. Richard L. van Houten, “HIV/AIDS in 2006,” REC Focus 6, no. 3–4 (December 2006), 7.

5. Michael Finkel, “Bedlam in the Blood: Malaria,” National Geographic, July 2007, 41.

6. Lee Eddleman, a personal mentor for four decades, observes that if suffering “leads us to a deeper sense of God’s lovingkindness, i.e., leads us to joy (cf. ‘who for the joy set before Him endured the cross’), then it becomes at least a blessing from Him” (personal correspondence).

7. Cf. Peter Hicks, The Message of Evil and Suffering (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2006), 141.

8. For one of her own many published comments see “Hope . . . the Best of Things,” in Suffering and the Sovereignty of God, ed. John Piper and Justin Taylor (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2006), 191–204.

9. All Scripture quotations in this chapter are taken from The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (ESV).

10. U.S. News and World Report, June 25, 2007, 39–42.

11. Though not always: see Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996).

12. See Alain Besançon’s book by that title, subtitled Communism, Nazism, and the Uniqueness of the Shoah (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2007).

13. Trinity, Spring 2007, 18–20.

14. “Facing My Questions,” Trinity, Spring 2007, 21–23. See chap. 10 of this volume.

15. Personal correspondence from Lee Eddleman, who adds, “For some the reality of the cross may suffice.”

16. No One Like Him: The Doctrine of God (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2001); The Many Faces of Evil (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1994); Where Is God? A Personal Story of Finding God in Grief and Suffering (Nashville: Broadman and Holman, 2004).

17. Classic Sermons on Suffering (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 1984).

18. See, e.g., Faith under Fire in Sudan (Newlands, South Africa: Frontline Fellowship, 1998).

19. Suffering and God: A Theological Reflection on the War in Sudan (Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa, 2002). Worth noting also is the fictional but true-to-fact rendering of the Sudan civil war by Philip Caputo, Acts of Faith (New York: Vintage, 2005).

20. Imprisoned in Iran: Love’s Victory over Fear (Seattle: YWAM, 2000).

21. Gary Witherall with Elizabeth Cody Newenhuyse, Total Abandon: The Powerful True Story of Life Lived in Radical Devotion to God (Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale, 2005).

22. Otets Arsenii, Father Arseny (1893–1973): Priest, Prisoner, Spiritual Father, trans. Vera Bouteneff (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 1.

23. For a recent slice of the discussion see David Van Biema and Jeff Chu, “Does God Want You to Be Rich?” Time, September 18, 2006, 48–56.

24. See Tarek Mitri, “Who Are the Christians of the Arab World?” International Review of Mission 89 (2000): 12–27.

25. January 3, 2003, http://www.samford.edu/News/news2003/010303_1.html (July 3, 2007), used by permission. Samford University dedicated a life-size bronze statue of Dr. Myers in May 2007. The statue is located in the university library in an area that houses the Marla Haas Corts Missionary Biography Collection.

26. This person remains anonymous for security reasons.

27. See, e.g., Christopher Hitchens, God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (New York: Twelve, 2007); Sam Harris, Letter to a Christian Nation (New York: Knopf, 2006); Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006).

28. See, e.g., Keith Ward, Is Religion Dangerous? (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007); Alister and Joanna Collicutt McGrath, The Dawkins Delusion? Atheist Fundamentalism and the Denial of the Divine (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2007); Michael Patrick Leahy, Letters to an Atheist (Spring Hill, TN: Harpeth River Press, 2007).

29. See John W. Cooper, Panentheism: The Other God of the Philosophers (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2006).

30. Pointing in fruitful directions is, e.g., Kevin J. Vanhoozer, The Drama of Doctrine: A Canonical-Linguistic Approach to Christian Theology (Louisville: Westminster, 2005).

31. Apology, 50.

32. Reinhard Hütter, Suffering Divine Things, trans. Doug Stott (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000), 31.

33. Ibid., 30 (Hütter’s emphasis).

34. Ibid., 31.

35. The connection between true knowledge of God and suffering aptly regarded may be disconcertingly direct. As Lee Eddleman observes (personal correspondence): “Deuteronomy teaches us that we are in constant danger of majoring on the wrong things; words and actions in themselves do not satisfy God. There is more. How does He get us there? Perhaps suffering?”

36. Cf. Hütter, Suffering Divine Things (p. 14), with reference to Heinrich Schlier’s realization of the poverty of German Protestant Christianity (rich in claims to personal piety but deficient in resolve to discover and live out biblical truth) at the time of the Third Reich. Hütter speaks aptly here of the “charismatic principle” and the “dogmatic principle.”

37. Ibid. Hütter is quoting Schlier.

38. Cf. Eric Young, “Episcopal Priest Suspended over Muslim-Christian Identity,” Christian Post Reporter, July 7, 2007, http://www.christianpost.com/article/20070707/28350_Episcopal_Priest_

Suspended_Over_Muslim-Christian_Identity.htm (July 9, 2007).

39. Cf. Stephen Keillor, God’s Judgments: Interpreting History and the Christian Faith (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2007).

40. See Christopher W. Morgan and Robert A. Peterson, eds., Hell Under Fire (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004).

41. Sibusiso Ngalwa, “Boy Dies Saving Friend from Crocodile,” April 4, 2004, http://www.iol. co.za/?click_id= 14&art_id=vn20040404110517366C649996&set_id=1 (July 10, 2007).

42. My thanks to Luke Yarbrough for consultation and corrections to an earlier draft of this chapter. I am also indebted to Lee Eddleman for helpful observations.

Suffering and the Goodness of God

Copyright © 2008 edited by Christopher W. Morgan and Robert A. Peterson

Published by Crossway Books, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers

1300 Crescent Street Wheaton, Illinois 60187

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law.