As a Christian who has worked for various Christian investment businesses, and who speaks often on topics related to Christian investing , I often run into a resistance point to the very idea that there could be any such things as Biblical investment strategies, because allegedly Jesus just doesn’t care or have anything to say about financial matters. I understand why they feel that way.

All too often, the pulpits are silent when it comes to Jesus’ economic messages. And all too often, usually high-profile religious broadcasters talk about money in ways that just don’t sound much like Jesus. But despite pulpits which are silent about money and broadcasters who engage in financial comment that don’t live up to what Jesus actually said, it’s important that we see how important the topic is to Jesus himself.

The Christian conversation about the life of Jesus has tended to default to the theological intent of His actions. In other words, Christ came to save us from our sins. Those are matters of the telos, the purpose of His life, in the eyes of the Father.

But other forces (Tax Collectors, Rabbis, Herodians, Romans) had different purposes (money, power, survival). The historical facts about their motivations do not contradict the theological truths about God's intentions. For example, the Gospels clearly say that the Sadducees at least partly wanted Jesus killed because He had become a threat to their livelihoods. But this in no way conflicts with the way that Jesus intended to turn their evil actions to a good purpose.

Some truths are on different levels from other truths. I point this out because sometimes when I talk to people about the economic dimensions of the Gospels, someone might get upset, because they think the economic level of explanation is being used to replace the theological level. It's obvious that these are not in conflict. But for some reason people occasionally view political, historical, material, and economic analysis as though it is an attempt to replace historic Christian doctrine.

But I would argue the opposite: that the historic doctrine of the incarnation (God taking on human nature) helps us to see all elements of His human nature operating in the Gospel accounts.

If He put on human nature, and not just a human body, then he put on every aspect of human life except sin. The view that he only took on a human body but not a full human mind is known as the heresy Apollinarism. The two ancient creeds which focus the most on the doctrine of the incarnation (the Athanasian Creed and the Chalcedonian Creed) both teach that the Son took on both human body and mind. Here's a quote from the Chalcedonian Creed, which is the ancient statement of doctrine which focused the most on the Incarnation:

"We, then, following the holy Fathers, all with one consent, teach men to confess one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, the same perfect in Godhead and also perfect in manhood; truly God and truly man, of a reasonable (rational) soul and body; consubstantial (coessential) with the Father according to the Godhead, and consubstantial with us according to the Manhood; in all things like unto us, without sin..."

Jesus had a reasonable, that is thinking, soul. Other than sin, He is 'in all things like unto us'. When He took on a body and a mind, he also took on a family, a village, a nation, its history. That includes the social and economic relationships that humans have. This view is not heresy; it is orthodoxy.

I wrote at greater length about it in this article (from which some sections above were adapted).

We have established the importance of historical detail, including economic and financial detail and now that we have established that taking these things into account is not in any way discouraged by sound theological doctrine, but rather encouraged by it.

Jesus Talked About Money and Wealth More Than He Talked About Sin

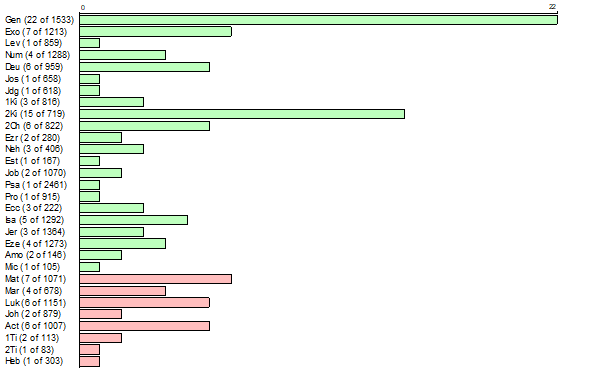

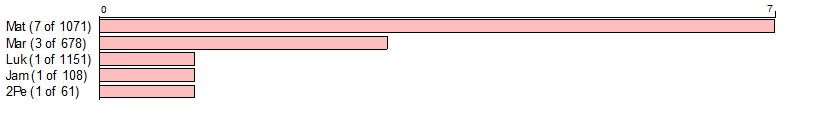

Here's a count of the appearances of the word 'money' in the NAS version of the Bible:

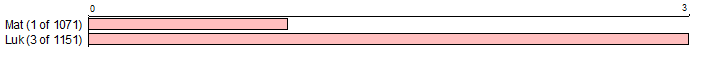

Here's a similar analysis of the alternate word, Mammon (a reference to money in its unrighteous usage, via reference to a pagan idol/demon of the same name):

Interestingly, Jesus’ use of the word ‘Mammon’, which is a negative portrayal of money, is a tiny proportion of all mentions of wealth and money. Four mentions of Mammon compared to nineteen mentions of money. This really throws into question the idea that Jesus is hostile to money (and by extension to Christian investment principles). I have often heard Christians, use the word ‘Mammon’ interchangeably with the word ‘money’ as though Jesus thought that money was inherently demonic. But his own practice undermines this. Money is Mammon only when it is worshipped.

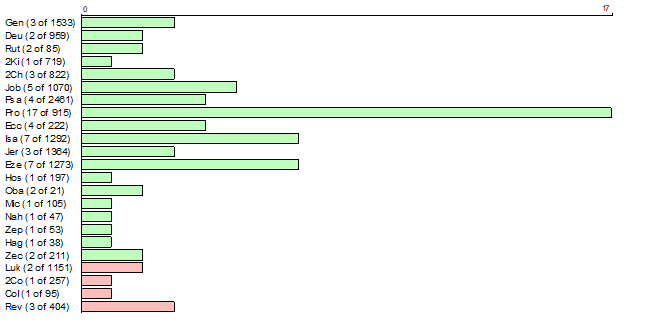

Since much of the Bible was written before the prevalence of money as a medium of exchange and accumulation of wealth, it may be helpful to look at the word 'wealth' as well.

That's 25 references in the Gospels alone to money, Mammon and wealth. It is a real focus of attention, and only occasionally of negative attention.

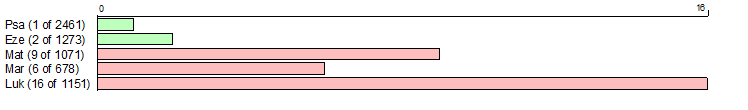

Here's the word count on ‘sin’:

That's 14 references in the Gospels to sin. At least going by how often he talked about it, money and wealth was a more important topic for Jesus than sin.

How about ‘hell’?

That's 11 Gospel references to hell.

It takes the topics of both sin AND hell to add up to the same numbers of verses which refer to wealth, money, and mammon.

It's obvious that Jesus cares quite a bit about the subject. A large number of Jesus’ parables are based on themes pertaining to money and wealth.

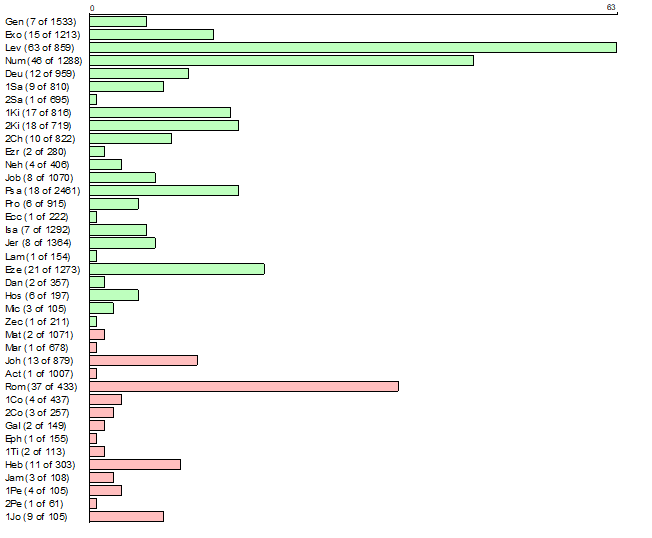

Parables are mentioned quite often in the Bible:

The word ‘parable’ is used 31 times in the Gospels. Arguably, that understates the prevalence of parables since some obvious parables such as 'the kingdom of God is like… a mustard seed… leaven… a householder… etc.' are clearly short parables, and the story of Lazarus the Rich Man is generally considered to be a parable but the word 'parable' is not used. The story of the Sheep and the Goats clearly has a message about wealth, but is not called a parable. So, the word count approach I used here underestimates the number of parables, and especially the number of parables with wealth as a major theme.

Roughly 20 of these references are to parables about wealth; specifically commerce, agriculture, stewardship, taxes, and similar topics. The rest refer mainly to household matters. This does not include the four examples above which are parables about wealth but do not use the word ‘wealth’. So, we have at least 24 parables in which wealth is a significant theme.

If we are to engage in truly Biblically responsible investment, we must start with the One about whom the Bible is written, Jesus. And before we choose Christian companies to invest in or Christian financial advisors, we must first see that Jesus has things to say about money and about wealth management.

Jerry Bowyer is a Forbes contributor, contributing editor of AffluentInvestor.com, and Senior Fellow in Business Economics at The Center for Cultural Leadership. He has had been a regular commentator on Fox Business News and Fox News. He was formerly a CNBC Contributor, has guest-hosted “The Kudlow Report”, and has written for CNBC.com, National Review Online, and The Wall Street Journal, as well as many other publications. Jerry lives in Pennsylvania with his wife, Susan, and the youngest three of their seven children.