Throngs of people streamed noisily past my dad and I as we stood outside the Yonge and Dundas entrance to Toronto’s Eaton Centre, Canada’s busiest mall. Though it was early spring, a winter chill still lingered in the air. Through a gap in the crowd my dad spotted a young woman about 25 metres away who appeared to be experiencing homelessness. She was bending down to retrieve something out of a bag at the south/west corner of Yonge and Dundas.

She was oblivious to the crowd, as it was to her. Dressed in old, dirty clothes, she looked a lonely and forlorn figure.

My dad approached her and introduced the two of us. “Excuse me,” he said to her with a smile and outstretched hand. “My name is Tim, and this is my daughter Leah. What’s your name?”

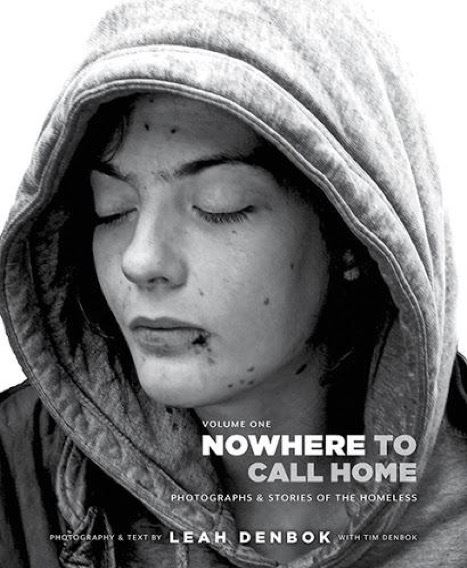

“I’m Lucy,” she answered in a quiet, shy voice as she shook our hands. My dad proceeded to tell Lucy that we were working on a book entitled Nowhere to Call Home. “Would you mind if Leah takes some pictures of you and I ask you a few questions?” he asked her. It will only take about 10 minutes. We’ll pay you $10.”

“Can you take my boyfriend Rylie’s picture too?” Lucy replied excitedly. When my dad said that we could, she ran south down Yonge Street to look for him. She returned about 10 minutes later with Rhylie in tow.

I set up my camera equipment beside the north wall of the Eaton Centre. It has a massive, lit-up, white sign that serves as a perfect backdrop. After Lucy had seated herself on a little ledge beside the sign, I began to snap some photos of her while my dad recorded the interview with her.

Lucy began by telling him that she once had big dreams. “I’ve always been a writer, like, journaling and short stories and what not,” she told him. “But now, it’s hard to keep up with the stuff you love, because it’s just survival.” Lucy told us that she became addicted to opioids when she was just a child. “I’ve been an opioid addict since I was fourteen,” she said, “but it was always manageable. I, like, had a job. I was going to school. I had my own place to live. I had interests.” However, one day she reached the point where her addiction took over her life. She found herself with no job, no schooling to speak of, and no place to live.

Though my dad and I have met several people experiencing homelessness who told us that they’ve managed to adapt to living outside in the, often, harsh Canadian elements, Lucy is not one of them. “I have a hard time with sleeping outside and stuff like that,” she said. “A lot of people, like, you know, they adjust....”

Not surprisingly, throughout my photo shoot with Lucy her eyes closed repeatedly. Lucy told us, excitedly, that she would soon be leaving the streets that she hates so much. “It’s transitional housing,” she said. “And I’m, like, moving in, in, like, three days. So I get my own bathroom, and I share a kitchen, and I’ll have my own bedroom.”

Sadly, this was not to be the case. For the following fall when my dad and I were again doing a photo shoot beside the Eaton Centre, we noticed Lucy and Rhylie sleeping on a broken up cardboard box in the middle of the sidewalk on Dundas Street. At one point during the photo shoot my dad noticed Lucy sit up and look around. He was shocked by her appearance. Though only in her twenties, she looked as if she was in her eighties. “How is she ever going to make it through the coming winter?” he thought to himself.

Photo Credit: Leah den Bok

The following spring my dad and I began to keep an eye open for Lucy. My book had come out—with Lucy’s photo on the cover—and I wanted to give her a copy. However, despite the fact that my dad and I did several photo shoots of people experiencing homelessness outside of the Eaton Centre, Lucy was nowhere to be found. “I hope Lucy made it through the winter,” my dad commented to me after a futile search for her.

But then, in the summer of 2018—much to our relief—my dad and I came across Lucy and Rhylie squeegeeing car windows at the corner of Yonge and Dundas streets. When I gave her a copy of my book she was jubilant. She jumped up and down yelling, “Woohoo.” It was very rewarding to me to be able to bring a little bit of happiness into the life of this woman who, though still young, had known so much misery.

Several months later, as the season began to change from summer to fall, we, again, encountered Lucy beside the Eaton Centre. We were pleasantly surprised to see how nicely she was dressed. Smiling, she told us that she was finally off the street. “I’m living at a women’s shelter,” she told us. She said that Rhylie, too, had a place to stay. After we had said goodbye to Lucy and were beginning to walk away, she said:

“This is a good thing that you two are doing!"

In the winter of 2019 my dad and I came across Rhylie once again outside of the Eaton Centre. Only this time he was alone. From the expression on Rhylie’s face we knew immediately that something was wrong. “Lucy’s in the hospital,” he told us. As tears began to well up in his eyes, he said, “She’s not doing very well.” Before we said goodbye to Rhylie, he said something that I will never forget: “Thank you so much for putting Lucy on the cover of your book. It made her feel human.” (Unfortunately, we didn’t think, at the time, to ask Rhylie for the name of the hospital where Lucy was a patient, and so was unable to visit her before heading back to our home in Collingwood.)

In April of 2019 a producer with a major media outlet expressed interest in doing a story about the positive influence that my cover photo of Lucy has had upon her. But first we needed her permission. We spent about a month looking for Lucy, but without success. A disturbing question kept forcing itself into our minds: “Was Lucy still alive?” But then, in May, we got a lucky break. While doing a photo shoot of a young woman, named Diamond at a safe injection site in Toronto, we discovered that she is a friend of Lucy’s. Diamond promised us that she would pass our contact information on to Lucy.

The very next day, when my dad returned home from work, there was a voice mail on our answering machine from Lucy. When he called her back she told us that she was doing well and that Rhylie and her were sharing an apartment together. She also told us that she had managed, with help, to get her drug problem under control. She had even begun writing again. When my dad told Lucy about the possible news story, she was positively ecstatic.

Because someone took the time to care and share her story, Lucy has chosen life.

Later that day my dad received an email from Rhylie saying:

“I can't begin to thank you enough! Partly because your book exists and the fact that you chose Lucy to be on the cover are the reason that we are both alive today! At the time of your photographs I think that the both of us had given up on life! Now we have both chosen to live! We no longer smoke crack cocaine which was difficult to say the least! Lucy is now at a healthy weight and I think that she's happier than she's been in a very long time. I know that I am! We are both currently housed and we are both on our way to being healthy again in mind, body and health!”

Editor's note: "Who Cares - Fred Forster" video features Leah den Bok's photographs of the homeless

Leah den Bok, an internationally-known photographer, has been travelling the world photographing and—with her dad's help (Tim den Bok)—recording the stories of people experiencing homelessness. She is the author, along with Tim, of two books entitled Nowhere to Call Home--Photographs and Stories of People Experiencing Homelessness, Volumes One and Two. The third volume, which is due out this fall, is being published by Austin Macauley Publishers in NY. Leah's two goals with these books are: first, to humanize people experiencing homelessness, and second, to shine a spotlight on the problem of homelessness. Not wishing to profit off of the misery of others, Leah donates 100% of the profits from the sale of her books (and photographs) of people experiencing homelessness to homeless shelters. Follow Leah den Bok's photographs on her 'Humanizing the Homeless' Instagram here.

Leah den Bok, an internationally-known photographer, has been travelling the world photographing and—with her dad's help (Tim den Bok)—recording the stories of people experiencing homelessness. She is the author, along with Tim, of two books entitled Nowhere to Call Home--Photographs and Stories of People Experiencing Homelessness, Volumes One and Two. The third volume, which is due out this fall, is being published by Austin Macauley Publishers in NY. Leah's two goals with these books are: first, to humanize people experiencing homelessness, and second, to shine a spotlight on the problem of homelessness. Not wishing to profit off of the misery of others, Leah donates 100% of the profits from the sale of her books (and photographs) of people experiencing homelessness to homeless shelters. Follow Leah den Bok's photographs on her 'Humanizing the Homeless' Instagram here.

Photo Credit: ©GettyImages/scyther5.jpg