4 Lessons C.S. Lewis and Sigmund Freud Can Teach Us in Freud’s Last Session

Sigmund is an aging man known as the world's leading atheist. His books on psychoanalysis are read worldwide. His books are studied in classrooms, too.

Sigmund is also a dying man who wants to spend one of his final days chatting with the world's foremost defenders of Christianity -- a man known among acquaintances as "Jack."

Perhaps neither man will convince the other. Nevertheless, Sigmund believes it would be a delightful conversation. Thus, Sigmund (that's Sigmund Freud) invites Jack (that's C.S Lewis) over to his house for a midday chat.

How will it go?

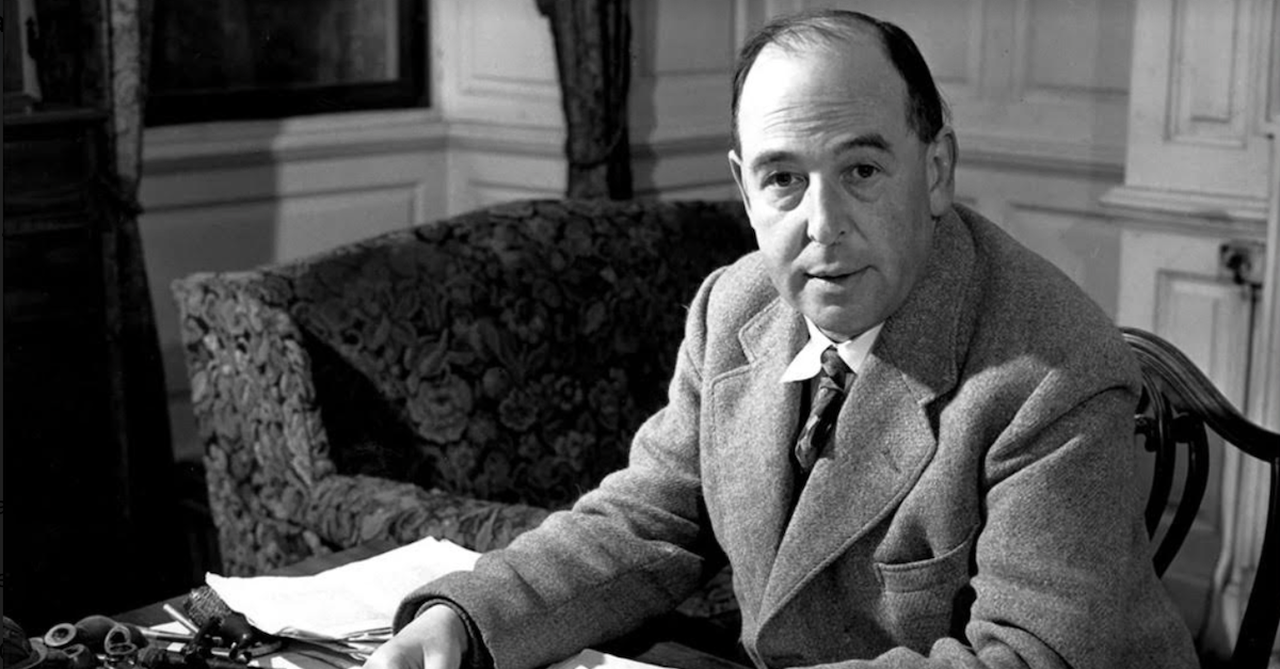

The new movie Freud's Last Session (PG-13) tells the story of an elderly Freud debating and even befriending a young Lewis in the late 1930s as war spread across Europe. The plot is likely fictional, although in real life, Freud did meet a young, unnamed Oxford professor shortly before he died. ("We will never know if it was C.S. Lewis," the film says.) It is based on a stage play and a book and stars Anthony Hopkins as Freud and Matthew Goode as Lewis.

The film has plenty of gospel-centric lessons for our supposedly modern culture. Here are four:

Photo credit: ©Sony; used with permission.

1. Civility Is a Virtue

1. Civility Is a Virtue

SLIDE 1 OF 4

The back-and-forth between Freud and Lewis likely wouldn't cut it on the nightly shows on MSNBC, CNN, and Fox News, where entertainment is king and the art of "debate" involves shouting, straw men, and endless non-sequiturs.

In Freud's Last Session, we watch two intellectual titans disagree without being disagreeable. We watch two men exchange points and counterpoints without going to blows. And they do all this while debating a subject -- faith -- that is far more significant than what passes as "news" in our world.

At the beginning of the film, Freud wonders how someone of Lewis' "supreme intellect" could "suddenly abandon truth and then embrace a ludicrous dream, an insidious lie" -- a reference to Lewis' embrace of Christianity.

"Have you ever considered how terrifying it would be to realize that you're wrong?" Lewis retorts. He adds, "There is a God, and man doesn't have to be an imbecile to believe in Him."

At the end of the discussion, Freud smiles and -- with a twinkle in his eye -- tells Lewis, "Welcome to my den." He even offers him a drink.

They're opponents in the battle of worldviews but not enemies in a real-world war. They understand that the art of persuasion requires civility. Lewis, of course, has a gospel incentive, wanting to practice humility and the spirit of Scripture: "The wise are known for their understanding, and pleasant words are persuasive" Proverbs 16:21.

Photo credit: ©Sony; used with permission.

2. Patience Is Essential

2. Patience Is Essential

SLIDE 2 OF 4

You don't win many converts by interrupting others. You don't win many converts by shouting, either. Conversion involves the art of listening silently to those with whom you vehemently disagree and then calmly making a rational counterpoint. Conversion involves patience. It's a cousin of civility. The latter involves politeness and courteous behavior, while the former involves calm and composure. Both are essential.

From the opening minutes, Freud and Lewis seem to be at an impasse.

"Why am I here?" Lewis asks. To that, Freud responds, "Curiosity."

Each wants to persuade the other. Each also wants to understand the other. But to do that, each must be composed as the other speaks. Impatience would defeat their own respective cause.

Lewis knows he serves a God of patience (2 Peter 3:9) who requires patience from His church: "If someone asks about your hope as a believer, always be ready to explain it. But do this in a gentle and respectful way." (1 Peter 3:15-16)

Lewis is respectful. He's also patient.

Photo credit: ©Sony; used with permission.

3. It's Okay to Say, 'I Don't Know'

3. It's Okay to Say, 'I Don't Know'

SLIDE 3 OF 4

Christianity, at times, can be a paradox: We have the source of truth -- Scripture -- and yet we don't know the answer to every single question in life. Simply put: We're finite creatures serving an infinite God.

When Freud pins Lewis down rhetorically and questions why God allowed him to be diagnosed with cancer, Lewis responds solemnly, "I don't know."

"You don't know!?" Freud asks, surprised.

"I don't know, and I don't even pretend to know," Lewis answers.

Lewis practices humility. Yet, in areas where the Bible is clear, Lewis stands firm.

On sex and homosexuality, Lewis tells Freud, "There is a sexual code running through the Old and New Testaments that sex is to be shared between two people who are connected to each other."

When Freud asserts that Jesus was but a man, Lewis retorts, "Only Christ claimed to be the Messiah. He even claimed the power to forgive sins."

When Freud claims that God created evil, Lewis replies, "Who created prisons and slavery and bombs? Man. Suffering is the fault of man."

Lewis is incredulous that Freud's worldview does not allow for God.

"Why does religion make room for science but science refuses to make room for religion?" Lewis asks.

Lewis doesn't pretend to have every answer. But he also isn't afraid to speak the truth.

Photo credit: ©Sony; used with permission.

4. You Can Be Friends with Your Enemies

4. You Can Be Friends with Your Enemies

SLIDE 4 OF 4

During their worldview battle, Freud and Lewis don't sweep anything under the rug. On the contrary, they discuss a litany of hot-button issues: homosexuality, gender, sex, war, and the problem of evil, for starters. They debate the deity of Christ. They argue about the existence of God.

On nearly every topic, they hold polar opposite opinions. If they were in America, they'd likely be political enemies. And yet, throughout the film, they practice kindness and respect. They act as if they're friends.

When Lewis undergoes a panic attack during a German bombing raid, Freud comforts him, encouraging him to remain calm. (Lewis, who fought in World War I, is terrified of loud sounds.) When Freud experiences severe pain due to advanced mouth cancer, Lewis expresses true sorrow and tries to help him any way he can.

Lewis and Freud take to heart a fact many of us have forgotten: We may have our differences, but we have a shared humanity. We all struggle. We all face trials. We're all searching for answers. We all need love. We may come from different cultures, but we have a lot in common nonetheless.

Lewis' beliefs are driven by something even deeper: his belief that Freud is made in God's image. If the Creator of the universe loves an atheist like Sigmund Freud, then Lewis should, too.

Freud's Last Session is a charming throwback to a time before social media, before 24-7 news. It demonstrates what debate should look like: a mutual exchange of ideas where both parties try to understand the other, and neither side has a hidden agenda.

Lewis and Freud work as hard to find agreement as disagreement. They enjoy one another's company. In fact, it's easy to imagine them becoming great friends.

We could learn a lot from them.

Freud’s Last Session is rated PG-13 for thematic material, some bloody/violent images, sexual material and smoking. What parents should know: Freud discusses sex in medical, yet explicit, terms. His daughter is a lesbian and, toward the end of the film, brings her partner home to meet him. The film contains minor coarse language (d--n 4, G-d 1, b-----ds 2).

Entertainment rating: 4 out of 5 stars

Family-friendly rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars.

Photo credit: ©Sony; used with permission.

Michael Foust has covered the intersection of faith and news for 20 years. His stories have appeared in Baptist Press, Christianity Today, The Christian Post, the Leaf-Chronicle, the Toronto Star and the Knoxville News-Sentinel.

Listen to Michael's Podcast! He is the host of Crosswalk Talk, a podcast where he talks with Christian movie stars, musicians, directors, and more. Hear how famous Christian figures keep their faith a priority in Hollywood and discover the best Christian movies, books, television, and other entertainment. You can find Crosswalk Talk on LifeAudio.com, or subscribe on Apple or Spotify so you never miss an interview that will be sure to encourage your faith.

Originally published December 27, 2023.