Hitting Heretics, Turning Tables, and Asking, “What Would Jesus Do?”

Legend has it that Saint Nicholas (the original Santa Claus) slapped Arius in front of hundreds of bishops at the council of Nicaea. Why? Because Arius was actively promoting the heresy that Christ was only a created being—like God, but not one with him.

In this tale of the kingdom of heaven suffering violence, Nicholas counters with a zealous violence of his own, memorialized not only in Greek iconography, but also in numerous memes that circulate online, especially during the holiday season.

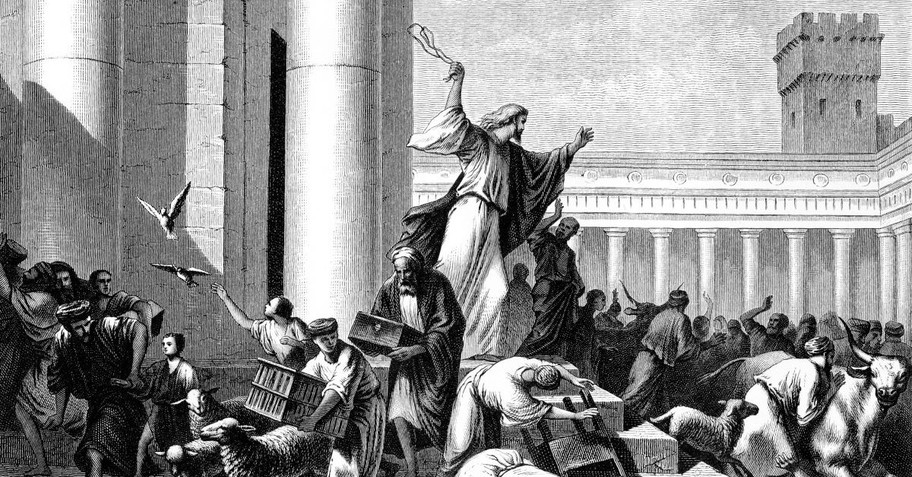

Speaking of provocative Christian memes, there is one funny example that states the following: “If anyone asks you ‘What would Jesus do?’ remind him that flipping over tables and chasing people with a whip is within the realm of possibilities.”

The joke provides a good laugh. But, like many Saint Nicholas memes, it also introduces a question: how should we respond to false teaching and dishonest worship? Are followers of Christ to imitate him in all he does, including table flipping?

Photo Credit: ©iStock/Getty Images Plus/camaralenta

What Would Jesus Do?

Let’s look at two of the most familiar Scripture verses about imitating our Savior. The first is 1 Peter 2:21: “To this you were called, because Christ suffered for you, leaving you an example, that you should follow in his steps.”

This is not just a generic exhortation. The context of this verse is the suffering of Christ at the hands of his opponents. As the previous verse states, “But if you suffer for doing good and you endure it, this is commendable before God” (v. 20).

In this passage, Peter gives us some specific examples to emulate: in his unjust suffering, Christ did not practice deceit (v. 22), nor did he return insults with insults of his own (v. 23), nor did he make any threats (v. 23). In these ways, he refused to reciprocate the actions of his enemies. Instead, he “entrusted himself to him who judges justly” (v. 23). We are called to do likewise.

The next Scripture verse about imitating our Savior comes from Jesus himself: “I have set you an example that you should do as I have done for you” (John 13:15). What example had he set in this passage? Well, he had just turned the tables (so to speak) on his disciples: he whose sandals none of his disciples were worthy to untie (John 1:27) had taken the lowliest position in the room—that of a servant—and washed the dirt and dung off his disciples’ feet.

In this passage, the King of kings and Lord of lords (Rev. 19:16) is not laying down a carte blanche command to imitate him in everything he did—that would be usurpation, not imitation. Rather, Jesus is giving a localized command (serve others sacrificially), with a specific heart posture in mind (humility).

In both of the examples above, we are not given a blank check to do with as we please, but a specific set of funds for a distinct course of action.

The Distortion of Anger

The (legitimately humorous) image of a bishop punching a heretic’s lights out is a poor excuse for Christian imitation, in light of the passages above. It suggests that a believer can be so enthralled in the purity of his heart with the honor of God’s name that the most holy course of action is to do violence to perpetrators of heterodoxy. Such a scenario does not match biblical reality, in part because of what Scripture says about human anger.

Love born of God is “not easily angered” (1 Cor. 13:5). Consequently, on seven separate occasions (in the NIV), God’s nature is described as “slow to anger” and “abounding in love.” Furthermore, in the over 3,700 verses in the gospels, Jesus demonstrates righteous anger for an approximate total of 30 verses. (That’s less than 1% of Christ’s recorded public ministry.) And in Luke 19:41 specifically, we read that Christ’s whip-wielding in the temple was preceded by his weeping over the city. How often does our anger, like that of our Savior, rise slowly out of a bed of tears?

Evidently, not too often. In fact, Scripture informs us that “human anger does not produce the righteousness that God desires” (James 1:20). That doesn’t mean righteous anger is an impossibility—just that it’s more rare than we would care to admit. And even in cases of righteous anger, Ephesians 4:26 commands us to cease being angry before the day’s end. Even in its legitimate form, anger cannot remain in a prolonged state without succumbing to sinful expressions.

What’s more, anger aimed at the right object can still be fraught with peril, as explained in the book Untangling Emotions: “You are in the greatest danger [of sinful anger] when you are right, because being right about someone else’s sin so easily blinds you to your own” (p. 177). How much more slow to anger should we be than our Lord!

It is not hypocritical for the Judge of all the earth to forbid us from imitating him in his wrath (Rom. 12:19) or his vengeance (Deut. 32:35; Heb. 10:30) or his omniscience (Isa. 29:16; Rom. 9:20) or his sovereignty (James 4:13-17). That we are called to imitate Christ (1 John 2:6) and be conformed to his image (Rom. 8:29) is not an invitation to become his equal (Psalms 8:3-4; Isa. 40:17) or to conform him to our image (Psalms 50:21).

Even if there were a case where it was appropriate for someone to imitate Jesus in a “cleansing the temple” sort of way, it would not be the person eagerly pantomiming the proper whipping technique. Nine times out of ten (give or take a few), the person looking to table-flipping Jesus as an imitable example is really looking for an excuse to play God rather than be like him. Underneath their pretense of “What would Jesus do?” is the real question holding sway: “If God did it, why can’t I do it too?”

Photo Credit: ©GettyImages/wynnter

A Truth Better Than Legend

To return to where we started, the appeal of a punchy Saint Nick is explained by Steven D. Greydanus:

In this era of safe spaces, trigger warnings and microaggressions, many people find tough-talking and even hard-hitting honesty refreshing and welcome. The image of St. Nicholas punching Arius is appealing to many because it’s so patently politically incorrect — a rebuke, in the eyes of some Catholics [and Protestants], to what they disparagingly call the “Church of Nice.”

One problem with this legend, however, is that it is a fabrication. Nicholas didn’t slap Arius—or anyone else, for that matter. “The story has no historical value,” writes Greydanus, as “Nicholas is linked to the Council by much later hagiographical works written over half a millennium after Nicholas died.”

In his book The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus, Adam C. English writes that this story of Nicholas slapping Arius was circulated by those who “wanted to prove that their hero, Nicholas, was one of the key defenders of the faith at Nicaea” because he was willing to “steamroll his enemies” (p. 107). However, says English, such a story displays “none of the compassion and tenderness and concern for which Nicholas was so well known. . . . Instead of thundering down wrath on the heads of theological deviants, Nicholas shepherded them back into the fold with gentleness” (p. 107).

The specific deviant whom Nicholas did interact with was Theognis, “bishop of Nicaea and a major player in the events at the council” (p. 107)—as well as an Arius sympathizer. Theognis “irritated everyone with his stubbornness,” and yet Nicholas “wrote a string of letters to Theognis patiently persuading him of what was right. . . . He urged Theognis to put aside his pride and be reconciled with his fellow bishops” (pp. 108-109).

What was the result of Nicholas’ humble contending for the faith? “In the end, Theognis was convinced. . . . [He] submitted a letter of reconciliation and submission to the bishops…[and] affirmed in no uncertain terms the Creed of Nicaea” (p. 109).

Imitating Jesus by Imitating Saint Nicholas

The Knock-Your-Lights-Out version of Nicholas, as funny as he is, replaces one error (the “Church of Nice”) for another (the “Church of Mean”). The real Saint Nicholas avoided both. He did not confront heresy with physical violence or human anger. He did not “wage war as the world does” (2 Cor. 10:3). Instead, he called Theognis back to orthodoxy (right thinking) through a proper orthopraxy (right behavior). He had a much nobler goal than merely winning an argument; he sought to win his opponent:

And the Lord’s servant must not be quarrelsome but kind to everyone, able to teach, patiently enduring evil, correcting his opponents with gentleness. God may perhaps grant them repentance leading to a knowledge of the truth, and they may come to their senses and escape from the snare of the devil, after being captured by him to do his will. (2 Tim. 2:24-26)

At times, a true servant of the Lord will be involved in “correcting his opponents.” But will it be with a glint in his eye and a fist in his opponent’s face? No, but rather “with gentleness” (see also Gal. 6:1, 1 Pet. 3:15).

It is worldly wisdom that imagines a contradiction between gentleness and rebuke, as if we can only have one or the other. But the latter cannot rightly be practiced without the former. Indeed, the one time in all of Scripture in which Jesus described the core of his being, he said, “I am gentle and humble in heart” (Matt. 11:29).

“Gentle and humble” is the mold in which every disciple’s heart should be formed—not “slap-happy and punch-drunk” (not literally, anyway). A Christian’s heart should, like that of Saint Nicholas, refuse to thunder down wrath on its opponents, but call them to the truth with a humble gentleness.

Sources Cited:

Groves, J. Alasdair, and Winston T. Smith. Untangling Emotions. Crossway, 2019.

English, Adam C. The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus. Baylor University Press, 2012.

Photo Credit: ©Getty Images/Wideonet

Originally published December 19, 2023.