Featured

A Prayer of Surrender - Your Daily Prayer - May 2

We must be still. We must surrender the entire difficult situation and its unknown outcome and every detail of it to the Lord, the one who fights for you.

Continue Reading...

Today's Bible Reading

Day 122: Acts 15:1-21; Joshua 23-24; Job 32

Verse of the Day

Daniel 3:17-18

If we are thrown into the blazing furnace, the God we serve is able to deliver us from it, and he will deliver us from Your Majesty’s hand.

Read Daniel 3Most Popular

7 Daily Wellness Practices Rooted in Scripture

Slideshows

The Power of Names - Your Nightly Prayer

Your Nightly Prayer

7 Reminders That You’re Never Too Old to Make an Eternal Impact

Slideshows

Our Faithful Provider - The Crosswalk Devotional - May 1

The Crosswalk DevotionalPlus

Video

Loading...

For Plus Subscribers

Today's Inspiring Video

Video

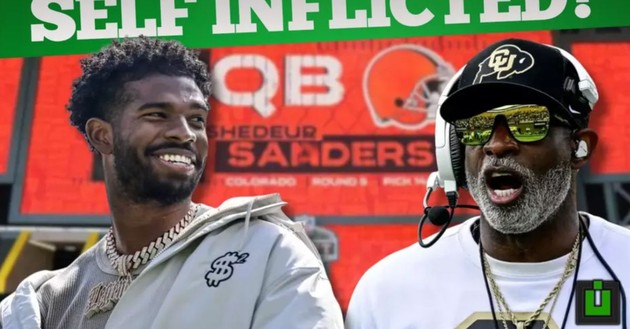

How Shedeur Sanders' Perception Caused Him to Slide - NFL Draft Recap 2025 | UNPACKIN' it Podcast